First-time visitors to the University of Mississippi campus are usually struck by its incredible beauty.

People like me who have walked over it for most of their lives also have moments when the sunlight hits a certain spot just right and it takes your breath away. I find that happens a lot on autumn weekday afternoons when I stroll from the Lyceum to Ventress Hall and through the heart of the Grove.

It wasn’t chance or simply the natural state of the terrain and plant life that has lead to Ole Miss being perennially named among the most beautiful college campuses in America. Rather, it was the fruit of the efforts of several well-respected architects who shaped the university’s growth from the 1840s through the 1970s, and also a focus on the looks of the place by former Chancellor Robert Khayat. There’s also the tireless work by the UM groundskeepers overs the years.

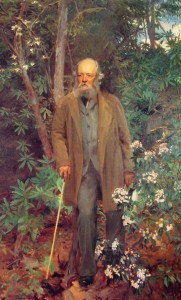

The firm started by Frederick Law Olmsted, who was kind of a big deal in his day, was hired to design a campus master plan, which shaped the modern appearance of UM. Olmsted and his firm designed Central Park in the late 1850s, and also the grounds of both the White House and U.S. Capitol. Olmsted is sometimes called the father of American landscape architecture.

The university’s 2009 campus master plan gives some insight into how the Olmsted firm laid out its vision for the campus. The original planning and design was done in the 1840s by William Nichols, a celebrated architect in his own right who was responsible for Mississippi’s Old Capitol building and the Governor’s Mansion. Nichols designed the Lyceum to be the focus, with the Lyceum Circle to be the park-like space it is today. Decades later, the Olmsted family worked with Ole Miss for 25 years beginning in 1948, putting together several master plans, updates and other studies.

“The earliest plans of the Oxford campus developed by the Olmsted Brothers indicate development along the central ridge on an axis running east and west,” The 2009 UM master plan says. “Connections that link new development zones to the north and south were also suggested. A vocabulary of iconic open spaces defined by building edges reinforced the organizing principle established with Lyceum Circle. Roadways and parking were moved to the periphery of the central campus establishing a cohesive core academic area.”

Olmsted’s design of Central Park started in 1857 and his sons and other descendants continued the spirit of his work long after his death in 1903. The National Association for Olmsted Parks says Olmsted, his sons and his successor firm were responsible for creating more than 6,000 North American landscapes, which includes Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, Biltmore Estate in Asheville, N.C., Mount Royal in Montreal, the U.S. Capitol and White House grounds, among others. More than 1,900 files related to the Olmsteds’ UM work are kept at the National Park Service’s Olmsted Archives in Brookline, Mass.

“From Buffalo to Louisville, Atlanta to Seattle, Baltimore to Los Angeles, the Olmsteds’ work reflects a vision of American communities and American society still relevant today—a commitment to visually compelling and accessible green space that restores and nurtures the body and spirit of all people, regardless of their economic circumstances,” The National Association for Olmsted Parks says. “The Olmsteds believed in the restorative value of landscape and that parks can bring social improvement by promoting a greater sense of community and providing recreational opportunities, especially in urban environments.”

That “restorative value” the Olmsteds worked so hard to establish in so many places is evident to me each time I walk across this amazingly beautiful campus. We should all be thankful for their efforts.