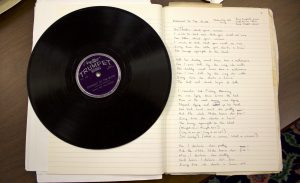

The items donated to the Blues Archive from the estate of Bill Donoghue include contracts, vintage recordings, decorative items and even food items related to Sonny Boy Williamson. Photo by Jimmy Thomas/UM Center for the Study of Southern Culture

OXFORD, Miss. – Sonny Boy Williamson soap and incense, test pressings of Memphis Slim and Buddy Holly records, and a signed contract by B.B. King are only a few of the many items recently donated by the family of William “Bill” Donoghue to the J.D. Williams Library at the University of Mississippi.

A man of many interests, Donoghue, who died in January 2017, was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, but settled in Seattle. He was a respected author and investment expert best known for his book and newsletter tracking the growth of money market mutual funds, who in 1980 wrote “William E. Donoghue’s Complete Money Market Guide” (Harper & Row), which reached No. 3 on The New York Times best seller list. He followed that successful first guide with a series of similar books.

But Donoghue’s other passion was Alex Miller, better known as Sonny Boy Williamson II, an American blues harmonica player, singer and songwriter. Williamson recorded with Elmore James on “Dust My Broom,” and some of his popular songs include “Don’t Start Me Talkin’,” “Checkin’ Up on My Baby” and “Help Me,” which became a standard recorded by many blues and rock artists. He toured Europe with the American Folk Blues Festival and recorded with English rockers including the Yardbirds and the Animals.

Bill Donoghue, an author and investment expert, was passionate about researching the life and career of blues artist Sonny Boy Williamson II. Submitted photo

Donoghue’s brother Ned said he was a great enthusiast for Williamson, as well as anything jazz or blues related that drew his attention.

“He swallowed mountains of data,” Ned Donoghue said of his brother, a longtime jazz and blues aficionado with an encyclopedic knowledge of the genres who became a leading authority on Williamson.

Bill Donoghue also maintained a website devoted to the musician, plus large collection of memorabilia. After conducting and recording interviews with more than 200 of Williamson’s friends and colleagues, Donoghue started writing a biography about the singer-songwriter titled “Hiding In the Spotlight: The Untold Story of Sonny Boy Williamson II.”

“His mysterious life is the stuff of legend and in my opinion, he was arguably the most colorful and overlooked character in American blues folklore,” Donoghue wrote in the introduction.

He goes on to write that his “obsession” with Williamson began in August 1995 while visiting Memphis for Elvis Week, when Living Blues magazine founder Jim O’Neal gave him a tour of the Delta, including Williamson’s gravesite.

After his brother’s death, Ned Donoghue wanted to find the proper place for Bill’s incredible amount of memorabilia, so he called the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and spoke with Katie McKee, the center’s director and an Ole Miss professor of English and Southern studies.

“I was moved and touched by one brother’s concern for another’s collection, so I put Ned in touch with Greg Johnson at the Blues Archive,” McKee said. “I believe it is here that the collection can be most accessible to the broadest range of scholars and be well taken care of by Greg.

Items from Bill Donoghue’s collection of blues memorabilia arrived at the J.D. Williams Library in dozens of boxes. The material has been inventoried and prepared for storage in the Blues Archive. Photo by Jimmy Thomas/UM Center for the Study of Southern Culture

“People look to the center as a starting place to see how other people study what is important to them, and the fun part of my job is connecting people who need to know each other.”

It is also fitting because Donoghue had done research at the university’s Blues Archive with Johnson, so it made sense for his collection to be in Oxford.

“I thought about the great literary and blues scholarship reputation the University of Mississippi has as an institution, and I knew Greg shared his enthusiasm for jazz and blues,” Ned Donoghue said.

“The Donoghue collection at the University of Mississippi will serve as a mecca for the music or popular culture scholar who seeks to immerse himself or herself or their-self in the largest and widest collection of primary and secondary source material conducive to interpreting the Mississippi Delta native, the man and the oeuvre and the legend that was Sonny Boy Williamson II.

“Ultimately, the most important elements for me are seeing that my brother gets the credit he’s due for carrying forward this important project to shine a light on Sonny Boy, and that Sonny Boy also gets the credit for artistry and the huge musical influence he had on the British Invasion of rock stars in the 1960s that Bill and others believe he is due.”

Bill Donoghue originally came to the university to conduct research on Trumpet Records. Photo by Jimmy Thomas/UM Center for the Study of Southern Culture

Donoghue originally came to campus to conduct research on Trumpet Records, which recorded a number of blues, gospel and rockabilly artists, said Johnson, the university’s blues curator and a professor in the Department of Archives and Special Collections.

“Bill came here because of the Trumpet Records collection, which was based in Jackson in 1950s and run by Lillian McMurry,” Johnson said. “She was the first person to record Sonny Boy and we have his recording contracts, royalty statements, correspondence and more.

“Bill looked at that and the Ivy Gladden Collection from Helena, Arkansas, which has the famous King Biscuit photos with Sonny Boy used to sell cornmeal.”

Johnson has fond memories of spending time with Donoghue in the archives.

“I remember him being just so excited about Sonny Boy; it was clearly his obsession,” Johnson said. “He had so many great anecdotes and he shared stories with me. He was really excited to see the Trumpet Collection. Seeing real source material is a powerful experience, and this was his passion.”

When the enormous collection arrived via truck from Seattle, Johnson said he was blown away.

The ‘Bring It On Home’ exhibit at the J.D. Williams Library includes a sampling of the vast collection of memorabilia donated to the university by the estate of Bill Donoghue. The exhibit is on display in the Department of Archives and Special Collections through early December. Photo by Greg Johnson/Department of Archives and Special Collections

“This is a huge collection with an awful lot of research and display potential,” he said. “There is great value to researchers and so many beautiful posters, photos and fliers. We can’t wait to put up the physical collection.

“Archives depend upon donations and the value of something like this is … who knows? Archives can’t go out and purchase things like this, so donations make it all possible.”

Luckily, Johnson isn’t the only one who will be able to see it, as the Department of Archives and Special Collections has opened an exhibit of the Donoghue Collection in the Faulkner Room. The exhibit, “Bring It On Home,” will run through early December.

But first, there was the task of cataloguing all the items.

Initially, Johnson went through all the sound recordings and books to inventory everything, creating spreadsheets and lists to see what filled in the gaps in the library’s collection, and placing everything into archival boxes and folders.

“The first thing I did was go through the 78s, put them in acid-free archival sleeves and type up the inventory,” he said. “Everything here will be put into a finding aid so researchers can see what we have and what to request.

“We are already several months into it, and there will be a series of refining the collection. We’ll get an initial finding aid up and it will be roughly organized, then we’ll narrow it down to add more granularity to the descriptions.”

Johnson and the Donoghue family all look forward to showing off the collection.

“The good thing is all of this will be made available and accessible to the public,” Johnson said. “It is mostly blues, and some jazz with some video and audio interviews with transcripts.

“We are processing and typing up an inventory and then we’ll refine it and properly digitize the VHS tapes. There is a lot to go through, but I’m excited about the exhibit to show all this off.”