The Harvell family – (from left) Joe, Felicia, Joseph Andrew and Ashley – all attended the University of Mississippi. Submitted photo

OXFORD, Miss. – When civil rights activist James Meredith (BA 63) integrated the University of Mississippi in 1962, he made it possible for thousands of other Black people to follow him, including his late son Joseph, who received a doctorate in business administration in 2002, and granddaughter Jasmine, who received a master’s degree in integrated marketing communication in May.

Other generations of Black families have chosen to be a part of the university for its affordability, academic opportunities, athletics scholarships and proximity to family. Some have been part of the university long enough to witness the growth of its welcoming environment.

“I am privileged to watch my daughters (Jasmine and Janelle Minor) excel in a place that their grandfather was barred from because of the color of his skin,” said Ethel Young Scurlock, dean of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College and associate professor of English and African American studies, who joined the UM faculty in 1996.

Janelle Minor (left), Ethel and Carlo Scurlock, and Jasmine Minor celebrate together at a Sugar Bowl event in January in New Orleans. Submitted photo

“They have benefited from the courageous work of James Meredith to make the University of Mississippi live up to its promise of educating all Mississippi citizens, without consideration of their race, gender and/or class.”

Janelle, a sophomore public policy leadership major, affirmed her mother’s comments.

“We get to be exactly what we came to this university to be: students,” she said.

The University Then

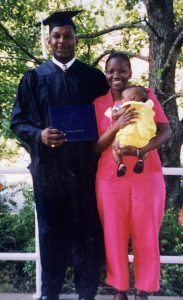

Joe and Felicia Harvell, and their children, Ashley and Joseph Andrew, all went to UM. Joe (BUS 93) was inducted into the Ole Miss Sports Hall of Fame in 2013 and serves on the M-Club and Ole Miss Alumni Association board of directors. He is area equipment manager for Yellow Freight in Memphis, Tennessee.

“I was recruited to Ole Miss to play basketball,” Joe said. “What got me to Ole Miss was the atmosphere. … It was a whole lot better than what I thought coming from the outside. And I was just welcomed with open arms.

“What I see now, which is impressive to me, is diversity at Ole Miss. When I was in school, you didn’t see that much.”

Felicia (BBA 91), a compliance adviser for Memphis-Shelby Schools, said she was familiar with Ole Miss because two older siblings attended the university.

Joe Harvell (left) was a star basketball player for the Ole Miss Rebels, but his wife, Felicia, remembers being ‘just a regular student’ during her time at the university. Submitted photo

“But my experience on the campus is definitely different (from Joe’s),” she said. “I was just a regular student.”

She shares that although there weren’t as many Black students at the university during her time, she has noticed a deep closeness to the friendships she forged as a student.

“When we come back to have our Black alumni reunions, we all know each other. It’s because we were so close.”

An Oxford native, Josh Davis (BBA 99) remembers selling Cokes in the Vaught-Hemingway Stadium during his junior high and high school years, surrounded by “a sea of Rebel flags.” He said he decided to go to UM because he couldn’t afford to go to the historically Black colleges and universities, or HBCU, college of his choice. However, he said he ended up enjoying his experience.

“I was really afforded the social capital that is a part of the Ole Miss connection, and have leveraged that heavily in my professional career,” said Davis, who worked at the university as coordinator of graduate activities, development officer for the College of Liberal Arts and assistant director of alumni affairs.

He recently moved back to Oxford and is vice president of policy and partnerships at StriveTogether, a national network of communities working to achieve racial equity and economic mobility.

Chancellor Emeritus Robert Khayat set the stage for change at the university, Davis said. His appointment as chancellor in 1995 happened to coincide with Davis’ freshman year.

“There was the immediate banning of the sticks in the football stadium, which, for all intents and purposes, began to eradicate the physical presence of the Confederate flags, and so that really set the tone for our incoming freshman year, to be able to feel encouraged and feel supported by the chancellor and the administration,” Davis said.

“It was important that inclusivity was being not just considered but embedded in policy. So even if we wouldn’t have articulated it that way, it was important for us, particularly as Black students, to be able to feel a sense of belonging.”

Ray Hawkins (left) celebrates his graduation from the university with his wife, Kathleen, and daughter, Ta’Nia. Submitted photo

Ray Hawkins (BA 01), who retired as chief of the UM Police Department last year, said the university was not his first college choice either.

“When I finished high school in 1983, the university was in turmoil over the election of the first African American cheerleader’s refusal to carry the Confederate flag,” Hawkins said. “I was very close to this situation because the cheerleader, John Hawkins, was my older brother.”

Hawkins opted to attend Mississippi Valley State, where another brother was a member of the Delta Devils baseball team. After two years in Itta Bena, he transferred to UM to be closer to home. He left the university in 1987, but returned to finish his degree.

Having been a part of the university, both as a student and employee, since the ’80s, Hawkins has witnessed its strengths, as well as growing pains.

“To me, the best thing about Ole Miss and why the university is able to attract talented students regardless of race or socioeconomic status is the academics,” he said. “Students are challenged to broaden their knowledge base and work to achieve their full intellectual potential. In the classroom, everyone has the same opportunity to be successful.

“Now, outside the classroom, socially, is where you see the distinguishable difference in race and socioeconomic status. But even with the noticeable differences in resources and availability to outlets outside the classroom, marginalized groups (still) manage to create an environment where they have a voice and can thrive.

“The racial overtones that have existed throughout the history of the university still seem to linger even though the university has addressed some of the symbolism of its controversial past. But every step, even small ones, are steps in the right direction, and hopefully one day, the university will be known as a truly diverse and inclusive institution free from its (racist) past.”

The University Now

For more recent graduates and current students who were interviewed, their experiences seem to differ from their parents and mostly paint a picture depicting positive change.

Janelle Minor (left), a sophomore public policy leadership major, spends time with her mother, Ethel Scurlock, dean of the university’s Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Submitted photo

“I have been able to see so much rapid change, especially with regards to the removal of Confederate symbols,” Janelle Minor said. “Of course, individual students or independent organizations may still find a way to uphold ‘old South’ traditions and Confederate memorabilia, but overall, I don’t see that represented in actual university policy.”

Janelle said she has loved her student experience so far.

“As a member of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College and Trent Lott Leadership Institute, I have been able to take classes from iconic Mississippians like (former representative) Chip Pickering and (journalist) Curtis Wilkie,” she said.

“I also have the opportunity to learn from professors that are leaders in their field. I cannot rate my experience highly enough. I love this university, and I know that this place is home.”

Scurlock’s older daughter, Jasmine Minor (BA 19), also said she had a good experience at UM.

“Through the university, and opportunities afforded to me through university-affiliated organizations, I found my closest friends, my voice and the passion that drives me to do poverty alleviation work as my full-time job,” Jasmine said.

As an African American studies major, she was a member of Bridge STEM, Increasing Minority Access to Graduate Education, the Black Student Union, E.S.T.E.E.M., the Center for Inclusion and Cross Cultural Engagement’s iTeam and Delta Sigma Theta. Jasmine also served as a MOST mentor. She is an operations assistant for UpRise Nashville, a career development program in Tennessee.

The Harvell family – (from left) Joe, Felicia, Ashley and Joseph Andrew – attend an Ole Miss football game in 2016. Submitted photo

Siblings Ashley and Joseph Andrew Harvell, who were both members of the Black Student Union, as was their mom, took advantage of a tool their parents did not have while in school. They both used Twitter to connect with other prospective students before they applied for admission to Ole Miss.

When typing in a hashtag, “thousands of people popped up,” said Ashley (BSN 15), who works in the acute pulmonary unit at University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas. She said she was pleasantly surprised to find those thousands of people included prospective and incoming students not only from Mississippi, but places as far away as California, Florida and New York.

“I just reached out to them, actually became friends with a lot of people that were going to Ole Miss. I was like, ‘OK, this is my decision.’ Once I got there, I made friends right away.”

Joseph Andrew (BS 20), who works as a technician at a medical research laboratory in Memphis, said he always knew that he wanted to go to Ole Miss because he grew up around it.

“My parents would always go to football, basketball games and everything,” he said. “So from a very young age, I knew I was going to Ole Miss, and when I was going in as a freshman, I did the same thing as my sister. I followed a lot of people that were going to Ole Miss, put in the hashtag ‘Ole Miss Class of 2020.’

“When I got there, I met a whole lot of people. It was very diverse. Everybody got along. Academically, I had a whole lot of chemistry, biology, because I (was) a dietetics and nutrition major. It was very easy to find study groups for all of those classes. I had no trouble making friends. And yeah, I loved it. It was a great experience.”

UM was not the first college choice for either Josh (left) or Reagan Davis, but both cherish their experiences on campus. Reagan particularly enjoys interactions with faculty members as a student. Submitted photo

Like Josh Davis, Reagan Davis did not want to go to UM.

“I did have the same mindset as my dad; I did not want to go here,” said Reagan, a sophomore public policy leadership major and outreach coordinator for the UM Pride Network.

“I wanted to go out of state; I wanted to get out of Oxford, just having grown up (there). But I decided to stay in Oxford because I did want to stay close to family. My parents have just built so many connections with people on and off campus. And I feel like within the Ole Miss community and the Oxford community, I have a family.”

Reagan said getting to talk with professors is one of the best aspects of the university.

“You can just go to their office hours to talk to them about anything,” she explained. “That’s something that I really like because I’ve gone to a couple of office hours for different professors.

“And whether it was just an exam coming up or a paper or something in my life, it just was really nice. I felt like there was a sense of connection.”

Ta’Nia Hawkins (right), an allied health studies major, says there’s no place like Ole Miss and is happy to have followed her dad, retired UPD Chief Ray Hawkins (BA 01), there. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

Unlike her dad, Ta’Nia Hawkins said UM was her first-choice university.

“The University of Mississippi has always been the school I wanted to attend,” said Ta’Nia, a Water Valley native and senior allied health studies major with a minor in chemistry. “From following my dad to work, to attending football games and other events on campus, I’ve spent a great part of my life here.

“I have a legacy here: My Uncle John, the first African American cheerleader; my Uncle Perry, U of M Hall of Fame; and my dad, Ray, first African American chief of police, all obtained their undergraduate degrees here. Ole Miss was also one of the few schools who wasn’t shy when it came to offering scholarships.”

Ta’Nia has been heavily involved in student organizations, including as vice president of Mortar Board, secretary of IMAGE, ambassador for the Health Professions Advising Office, head mentor of Brave Girls Ministry and member of the Chancellor’s Leadership Class. She also conducted research in Belize this past summer with the Louis Stokes Mississippi Alliance for Minority Participation program.

Jasmine Minor (right) celebrates her graduation from UM with her mother, Ethel Scurlock. Scurlock was director of African American studies when Jasmine completed her bachelor’s degree in African American studies in 2019. Submitted photo

“There’s no place like Ole Miss,” she said. “When I was in high school and I was going on college visits, no one had a welcome staff nearly as enthused as the Ole Miss Ambassadors. None of the campuses were as beautifully landscaped as Ole Miss.

“Even down to the application process, Ole Miss was one of the best, if not THE best, option in the state of Mississippi.”

Passing the Torch

Generational change and growth happen across all aspects of life/society, and UM is no exception. The personal stories of these four families provide a snapshot of how the Black student experience has transformed since James Meredith first enrolled at the university.

Scurlock acknowledges the role that a multitude of institutional programs and investments have played in creating a more welcoming environment on campus for all students.

“Now, we have a skilled team of leaders, working to create opportunities for students of all backgrounds to thrive at the University of Mississippi,” she said. “Because of their work, students are able to find a sense of belonging in this environment that was not available for previous generations.”