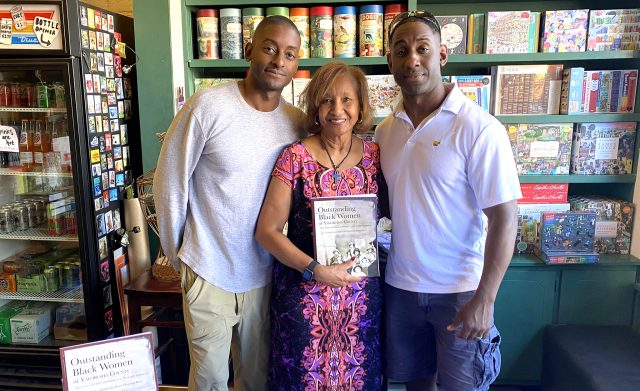

UM alumna Dottie Chapman Reed (center) is accompanied by her sons at a book-signing event for ‘Outstanding Black Women of Yalobusha County’ at Off Square Books in Oxford. The 2020 book grew from her oral preservation efforts and work with the university’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture. Submitted photo

OXFORD, Miss. – Dottie “Quaye” Chapman Reed (BA 74) was the first Black admissions counselor at the University of Mississippi, serving from from 1974 to 1977. Her extensive collection of papers will be on display at the UM Libraries’ Department of Archives and Special Collections through early March as part of the university’s commemoration of 60 years of integration.

The author of “Outstanding Black Women of Yalobusha County” (2020), Chapman Reed writes a column for the North Mississippi Herald highlighting histories of the area’s community members. She was also the first recipient of the Jeanette Jennings Trailblazer Award, named in honor of the university’s first Black faculty member.

Chapman Reed discussed her column, book and collection at the Two Museums in Jackson on Feb. 8. She also will be a panelist at the annual meeting of the Mississippi Historical Society in Jackson on March 2.

She also answered a few questions about her time at the university and her projects:

Tell me about your first experiences with the University of Mississippi.

I graduated from high school in 1970, and our junior and senior years were difficult and quite trying as we knew that we were going to be the last class to graduate from Davidson High School, the Black high school in Water Valley, as the schools would be integrated in the fall of 1970. Things were intense and filled with mixed emotions.

Dottie Chapman Reed speaks in September 2022 in the university’s J.D. Williams Library about her life story and efforts in oral history preservation. Photo by Thomas Graning/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

When I graduated, I wanted to get away from Mississippi as quickly as possible, (and) I went to Detroit with one of my girlfriends. She found a job and stayed. I couldn’t find a job; therefore, with no other options, I had to come back to Mississippi. My mom said, “Well, I guess you’re going to go to school.”

The night before registration opened, she drove me to Oxford to stay at the home of Miss Doxey Foster, a church friend. I spent the night and Miss Foster called Jennifer Jackson, a student who was already enrolled at Ole Miss, to come and pick me up and take me to campus. I was totally lost. I had nothing. I had no room, no financial aid, nothing.

Fortunately, when we got there, I ran into two friends from high school who took me by the hand, carried me down on the coliseum floor and got me registered for classes. I was able to enroll because I had attended pre-college in ’68 or ’69 based on an invite from my home girl, Beatrice Hawkins; therefore, I had basically already applied for admissions and was accepted.

What was it like to be an African American student at the University of Mississippi then?

As Black students in the ’70s and early ’80s, while we had our fears and concerns, we were a very close group. We knew each other, were organized and supportive of each other. We wanted everyone to succeed and got excited with the breakdown of each racial barrier.

Upperclassmen offered tutorial assistance through our adviser, (the) Rev. Wayne Johnson. He was our support system, mentor, encourager and lifesaver for many. The local Black pastors and community leaders were staunch supporters who opened not just the doors of their churches but the doors of their homes as well.

I could name many others who mentored and cared for us and trained us in leadership and community activism. They encouraged our enrollment and were proud of our successes at the university. We were quite impressed with the issues being addressed by the local legal services office in Oxford. We found role models, guidance and support from upperclassmen, from graduate and law students.

We had an active Black Student Union and a section in the Student Union where we congregated, where we developed comradery and strength when needed. The unity, brotherhood and closeness helped us succeed.

We were also encouraged as additional Black faculty came on board. The campus counseling center provided tutoring, testing and a class called Effective Study that proved to be helpful to some students.

How did you come to work in admissions?

As a student, my work-study job was in the computer center in Carrier Hall, and that’s where the guys from admissions would come to process grades and documents. I ran the keypunched data cards through the mainframe computer and did some of the key punching. I got to know those gentlemen, and they asked me if I wanted to work registration.

Dottie Chapman Reed (center) spends time with James Meredith (left) and the Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., a cousin of Emmitt Till, at The Inn at Ole Miss. Submitted photo

I started working registration under Dr. David Ross and Dr. Mamie Franks. I did various things, pulling cards for different classes on the coliseum floor or running errands between the computer center and the admissions office.

In my last semester, Ben Jones, a graduate student who was working with Dr. Ken Wooten in admissions, told me that they had decided to hire the first Black admissions counselor and encouraged me to apply. Being that I was getting ready to graduate, I thought, “OK, maybe I will apply.”

My basic goal was not so much to recruit students for the university, but to encourage young people to go to college and get a degree, and to know that if I did it, they could do it too, even from a predominantly white school, or that they could go anywhere they wanted to go. My gratification came in explaining to them the admissions and financial aid processes and answering whatever questions they had about college.

It was an interesting experience indeed, as I visited white schools and Black schools and integrated schools. It was at some of the white schools, in particular, that they were most surprised to see a Black person recruiting for the University of Mississippi.

It was also a learning experience for me in terms of learning how to give presentations, answer questions, travel across the state and into west Tennessee. Spending nights in hotels and eating at restaurants was all new to me. All and all, it prepared me for my career challenges and accomplishments in corporate America and beyond.

Tell me about the personal collection you donated to the University of Mississippi Libraries’ Department of Archives and Special Collections.

When I was in school, I kept a lot of clippings while at the university between 1970 and 1977. Whenever there was somebody Black in the Daily Mississippian, I kept the article – for example, if it was about the Black athletes, Blacks running for homecoming queen or others such as my roommate, Dorothy Balfour, who was one of the women who started the first Black sorority.

Even I wrote an article in the Daily Mississippian about the lack of financial aid for students in the summer.

The Rev. Wayne Johnson, our BSU adviser, had a little co-op store on Jackson Avenue and published a newspaper called the Soul Force. Black journalism students produced a publication called The Spectator. Copies of both newspapers are included in my collection. My collection also includes my trailblazer award, the award the students gave me when I left Ole Miss, an Ole Miss First award and my life to date beyond Ole Miss.

I decided to give my papers and memoirs to the library primarily for the education of the current students, for the generations to come and for my grandchildren. I have always felt the university needed to more intimately connected with the greater Black communities across the state, especially like the one that I came from only 18 miles away.

Only recently, did I become aware that quite a few people from Water Valley worked at the university as janitors, along with my first cousins, Senie and C.W. Willingham, who worked in the cafeteria, when I was in school. Because of their sacrifices and contributions, and those of many others, I hope my collection will help educate and recognize the early contributions of Blacks to the university.

What are your hopes for the future of the University of Mississippi and how does it compare to the institution you knew in the 1970s?

Based on my recent experience working with two former UM professors, Dr. Jessica Wilkerson and Dr. B. Brian Foster, over a three-year period, it would be great to see the university invest substantial funding to support community-driven research. The people of Mississippi, especially the Black communities, deserve more.

Dottie Chapman Reed (right) is greeted by former Ole Miss and NFL football player Curtis Weathers in September 2022 in the university’s J.D. Williams Library. Photo by Thomas Graning/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

Our “Black Families of Yalobusha County” project, which grew out of my collaboration with the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, and Dr. Jodi Skipper’s “Behind the Big House” project, in Holly Springs, are two examples of what can be accomplished on a shoestring budget. It would be proactive, instrumental and extremely beneficial for the surrounding communities if the university would fund projects like these.

Much like most predominantly white institutions nationwide, the university has made good progress in increasing minority accomplishments and achieving diversity in terms of enrollment, graduation, faculty, athletics and academic advancement. It has achieved numerous firsts that were not in place in the 1970s when I was a student and administrator.

Yet the need for further advancement, historical reconciliation and continued education exists.