OXFORD, Miss. – Before William Shakespeare created such literary and stage classics as

“Macbeth” and “Romeo and Juliet,” the legendary playwright may have labored over property deeds and other mundane legal documents.

Did Shakespeare work as an attorney before achieving immortality at the Globe Theatre? That’s one of the theories a University of Mississippi professor speculated on this week after he and three of his students compared a known signature by the Bard of Avon with another signature on the title page of “Archaionomia,” a well-known legal treatise housed at Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

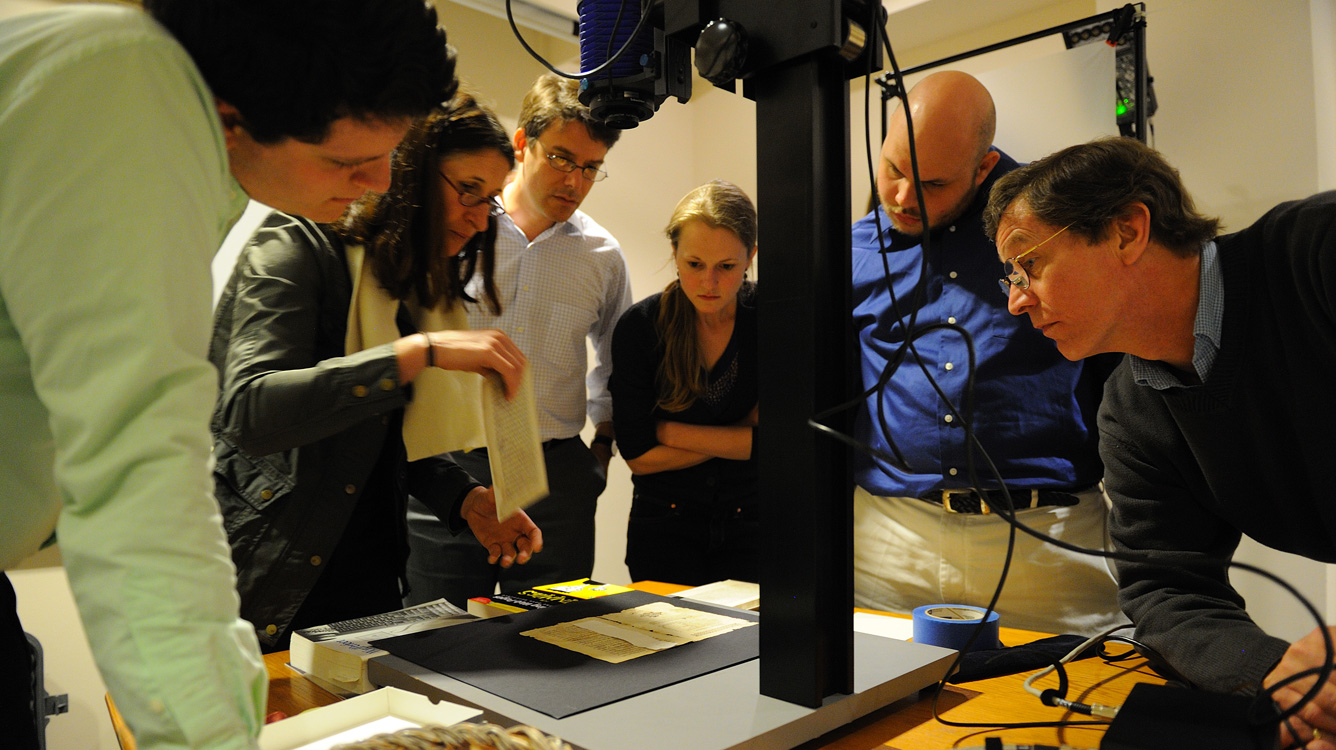

Renate Mesmer (second from left), head of conservation at the Folger Shakespeare Library, repositions the 'Archaionomia' under the imaging camera as (left to right) Mitchell Hobbs, Gregory Heyworth, Kristen Vise and Andrew Henning, all of the University of Mississippi, and William A. Christens-Barry, chief scientist with Equipoise Imaging, watch. UM photo by Robert Jordan.

Gregory Heyworth accompanied UM seniors Andrew Henning of Batesville, Mitchell Hobbs of Madison and Kristen Vise of Jackson, all students in the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College, to the nation’s capitol, where they spent their spring break studying the Folger documents. Using state-of-the-art digital imaging equipment, the Ole Miss team verified that the previously unknown signature is indeed from the same 17th century period as the playwright.

“We’ve gotten some clear results on the signature after image rendering earlier,” said Heyworth, associate professor of English and director of the Lazarus Project. “The clarity is significantly better than previous attempts. If it isn’t Shakespeare, it is at least a good forgery by someone who has seen Shakespeare’s signature firsthand.”

The imaging system uses a 50-megapixel camera and multispectral lights to photograph and analyze rare and aged documents. The previously barely legible signature was made visible after it was photographed under 12 different wavelengths of light and rendered using software traditionally used by geospatial scientists and the CIA. Once the team had the best possible photo, they superimposed it upon an authentic Shakespeare signature for comparison.

“Whether this is Shakespeare’s signature is something that we will not be able to determine for certain, perhaps ever, but we will have far better and more compelling data on which to make an adjudication,” Heyworth said.

Heather Wolfe, curator of manuscripts at Folger, said the facility is grateful to Heyworth, his students and the university for bringing their technology to the Folger collection.

“We won’t be able to verify that this is William Shakespeare’s signature,” Wolfe said. “But we may be able to determine that it was written in Shakespeare’s lifetime, by someone named William Shakespeare. There were multiple people with that name.

“The spectral fingerprint may indicate that it belongs to a forger, like William Henry Ireland in the 1790s. We are most excited about the possibility of using the technology to allow us to decipher the names of the spectral hundreds of 16th- and 17th-century former owners written on title pages, and subsequently crossed-out by later owners.”

The seniors were equally enthusiastic and excited about even the possibility of a discovery.

“While working on a senior honors thesis with Dr. Karen Raber on guilt and innocence in three of Shakespeare’s plays, I came across an old book on the subject where I found the lead on the Shakespeare signature at the Folger,” said Henning, an English major with a minor in mathematics. “The positive comparisons are phenomenal. For one, it suggests that, at the very least, Shakespeare possessed and was actively reading legal texts. Some might even argue that it draws a strong line indicating that Shakespeare was in some way involved in the English legal system.”

After graduation, Henning plans to attend graduate school at King’s College in London.

“I’ll be getting my degree in a field called digital humanities, where I’d like to focus on the very specialized area of manuscript recovery and restoration,” Henning said. “King’s College has the most established program in this area, so I’m elated that, through Dr. Heyworth’s help, I was able to get accepted. I intend to get my doctorate in the area as well.”

Students learn to use the cutting-edge technology in the project-based course “Image, Text and Technology” that Heyworth teaches at UM.

“Usually, my coursework doesn’t extend beyond the classroom, so to be involved in helping solve a question that’s bothered the Shakespeare community for much of the 20th century, I’m grateful and thrilled to be a part of such a process,” Hobbs said. The English major said he plans to attend the UM Medical Center in the fall.

A studio art/graphic design major, Vise has assisted Heyworth on other digital imaging projects. While each has been thrilling, she said the Shakespeare signature verification is especially rewarding.

“The match would provide evidence for the usefulness and possibilities of multispectral imaging and the cross-disciplinary nature of the field,” Vise said. “I want to work in a multidisciplinary field where overlap and collaboration are utilized to generate innovative solutions.”

Another means of verifying the signature lies in the spectral “fingerprint” of the ink.

“Every ink refracts light differently and uniquely,” Heyworth said. “Perhaps in the coming weeks, we will be able to compare the spectral fingerprint of this signature with other known and suspected Shakespeare signatures.”

Though once a lengthy process, this endeavor took less time than previous ones, thanks in part to the new equipment purchased by the Honors College for the Lazarus Project, Heyworth said.

“I want to thank Douglass Sullivan-Gonzalez for providing us with such incredibly powerful tools,” he said.

Sullivan-Gonzalez, dean of the Honors College, said he is more than glad to support Heyworth and his students in such worthwhile scholarly research efforts.

“The Lazarus project makes the experience of learning come alive,” he said. “A great professor engages undergraduate students to take their spring break and make a difference in the world of the academy. These students get a chance to see the past come alive in order to ask the right question about future research.”

The mission of the Lazarus Project is threefold: to facilitate manuscript recovery by providing researchers with access to multispectral technology, to train students and textual scholars in the use of multispectral technology and image rendering and in the scientific disciplines of the new codicology, and to collect data and metadata on damaged manuscripts as a basis for subsequent scholarship.

Since its inception, the project has analyzed several documents, including the Skipwith Revolutionary War Letters, which were donated to Ole Miss by Kate Skipwith and Mary Skipwith Buie, Gen. Nathanael Greene’s great-granddaughters; and the Wynn Faulkner Poetry Collection, 48 pages of early poetry written by William Faulkner between 1917 and 1925 that were donated by Leila Clark Wynn and Douglas C. Wynn. They were damaged and partly illegible, but honors students worked with multispectral imaging technology to recover several new poems.

Previously, Heyworth and another team of UM students used the lab to help restore “Les Esched d’Amour” (The Chess of Love), a long, 14th century Middle French poem. The unique medieval manuscript, damaged in a World War II attack, was believed too badly damaged to be recovered before Heyworth and Daniel O’Sullivan, associate professor of modern languages, began working on it under UV light seven years ago. In 2009, Heyworth and his students used the portable lab to photograph the most damaged portions of the text under light of various wavelengths. That analysis is ongoing.

Heyworth and his team are planning more projects, including a summer trip to Tbilisi, Georgia, to recover of some of the earliest copies of the Gospels and another to Milan, Italy, to help with the earliest manuscript of the “Book of Jubilees.” Heyworth and Susan Glisson, executive director of the university’s William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, also submitted a proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities for funds to establish a national civil and human rights archive at UM.

For more information about the Lazarus Project, go to http://www.honors.olemiss.edu/lazarus-project/.