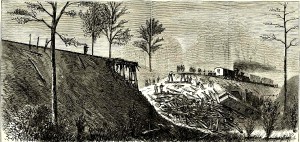

Harper’s Weekly ran this illustration of the first Buckner’s Trestle train crash in its March 19, 1870 edition.

The tree-lined Thacker Mountain Rail Trail that starts near the south end of Chucky Mullins Drive is a popular spot for hikers, cyclers and others who want to explore the 2.8-mile path.

But many don’t realize the tranquil path where UM’s cross country teams and campus ROTC groups sometimes run crosses Buckner’s Trestle, the site of two long-forgotten railway tragedies. In 1870, 20 people were killed in a crash there and another in 1928 injured many passengers, several whom were UM students and faculty members.

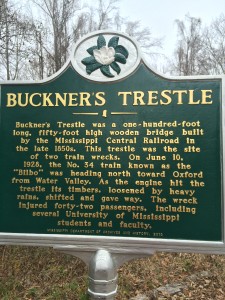

Buckner’s Trestle was a 100-foot-long railroad bridge that stood 50 feet high. The Mississippi Central Railroad built it in the late 1850s, but it’s no longer there. I walked by the Buckner’s Trestle crash site, and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History marker there, during a recent trip to the Thacker Mountain Rail Trail and decided to research it.

Not much can be found in online news articles about the more recent Buckner’s Trestle crash, which had no fatalities, but did injure more than 40 on June 10, 1928. The MDAH marker there says the No. 34 train, called “Bilbo,” was heading north to Oxford from Water Valley. When the engine crossed the trestle, the timber, which heavy rains had loosened from the earth, shifted and gave way. The train wrecked, injuring 42 passengers, including several UM faculty and students.

But the tragic Feb. 25, 1870 crash there made national news.

That day, the 3 p.m. mail train left Oxford bound for Water Valley. The engine, a baggage car, a mail car and the first passenger car made it across the trestle, but rotten ties gave way. The bridge collapsed and the trailing cars tumbled into a ravine. Twenty passengers were killed and 60 were injured. The crash was described in rich detail in Harper’s Weekly and also in The New York Times, as well as some regional newspapers.

J.W. Simonton wrote a vivid account of the crash for the New Orleans Picayune that ran in several U.S. newspapers.

Colonel Sam Tate, president of the Mississippi Central Railroad Company, was standing in the aisle of the rear car when the disaster happened, and was violently precipitated to the lower end of the coach, where he was nearly suffocated before the pile of wounded, confused and stunned passengers that were thrown upon him could be removed; but it is believed that he will sustain no permanent injury.

Some of the names could not be had. Two infants were among the number. One of these was taken from under the wreck, clasped with a death grasp to the bosom of its mother, who was also dead. Two colored brakemen were killed at their posts. One of these must have been thrown from the rear platform of the rear car, for he was found face down upon the roof of the coach lying in the ravine, his throat cut as if by a stout splinter.

The anguish of surviving friends of the killed and wounded was pitiable to behold. A husband, wild with grief at the loss of his wife, suddenly snatched from his side by death, just when he had nearly arrived at the home in the new world, which he had crossed the ocean to find, drew tears from eyes not used to weeping. The young girl, Abby Elliott, on her way to New Orleans, exhibited wonderful fortitude. She was in the rear of the middle passenger car conversing with several acquaintances, the life of the little circle surrounding her, when the crash came. In an instant the notes of mirth and frolic were turned to cries of anguish and lamentation. But Abby never lost her presence of mind for a moment. By her side lay several of the horribly mangled dead. Fortunately, no part of the wreck had struck her a deadly blow. Bruised she was, and stunned but no bone was broken. Her left hand rested upon the stiffening limb of one of the companions with whom she had been in gay conversation a minute before, and there it was held in a vice like grasp by a timber of the lower end of the rear passenger car. Otherwise she was free. Calling for help she stated her situation, and gave direction for her own relief. For an hour she lay there, exhibiting a patience and courage that were heroic. At last the timber was sawn asunder, her hand was released and she was carried away, piteously inquisting of those who were assisting her whether she was so hurt that she count not hope to be a future help to her “poor mother.”