Ole Miss student Clementina Ferraro (right), a member of Emily Cooley’s ‘From Farm to Fork’ LIBA 102 class, tries her hand at farming alongside Doug Davis, owner of Yokna Bottoms Farm. Photo by Emily Cooley/Department of Writing and Rhetoric

OXFORD, Miss. – Somewhat hidden in the vast University of Mississippi undergraduate catalog is Liberal Arts 102, a course offering stylized freshman composition courses with off-the-beaten-path topics.

From graphic novels and horror films to political history and the fundamentals of rhetoric, the classes fulfill the second half of the university’s general education composition requirement. Instructors bring their unique passions to first-year students – and turn the ordinary into the extraordinary.

The course, housed in the Department of Writing and Rhetoric, has existed for decades, with offerings changing each year. In 2018, a pilot program began pairing LIBA classes with the Provost Scholars Program, expanding its breadth. The Provost Scholar pilot will continue in the 2019-20 academic year as other LIBA courses remain open to all students.

“The Department of Writing and Rhetoric is proud to connect outstanding faculty to first-year students through the liberal arts seminar known as LIBA 102,” said Stephen Monroe, the department’s chair. “It has served thousands of UM students, and we plan to offer even more sections in the coming years, growing LIBA 102 to serve learning communities like the Provost Scholars.

“A small seminar led by a great teacher is still the best way for students to improve as writers, speakers and thinkers.”

Designed to prepare students for the challenges of college-level writing, the program was the brainchild of the late Carolyn Staton, provost emeritus, who modeled the course on the freshman seminar at Notre Dame. Faculty interest and expertise guided content while maintaining common learning goals in every section: to inspire critical thinking and offer students a range of uniquely appealing topics of study.

“LIBA 102 is a way for students to try on different ways of thinking and knowing, of getting to know the particular ways a given discipline studies the world,” said Angela Green, curriculum chair of LIBA 102. “We are lucky to have so many talented teachers willing to share their passion with first-year students and help light their way.”

From Farm to Fork

The little sticker on a banana might seem like nothing more than a barcode for scanning at the supermarket. But to the students in Emily Cooley’s LIBA class, “From Farm to Fork: Going Green Locally,” the code is key to unlocking a mystery of food sourcing – and a means to trace the banana from its origins and learn about its transportation, the factories involved in its farming, packaging and shipping, and its carbon footprint.

The purpose of Cooley’s course is to challenge students to consider the impact of their everyday decisions about food: on health, on their local community, and on the nation, world and environment. Students read about how food is grown, where it comes from and how it gets into our kitchens, considering both the benefits and challenges of local sourcing.

Students also explore the effects of corporate farming and the modern agribusiness model.

A field trip takes students in Emily Cooley’s LIBA 102 class to Oxford’s oldest community-supported agriculture farm, Yokna Bottoms. Photo by Emily Cooley/Department of Writing and Rhetoric

As part of the class, Cooley takes students on field trips to farms, farmer’s markets and restaurants that offer locally sourced food. Recent trips have visited several destinations, among them Yokna Bottoms, a community-supported agriculture farm owned by Doug Davis, UM associate professor of leadership and counselor education. The farm’s name is a reference to William Faulkner’s fictional Yoknopatawpha County.

Cooley also has taken students to Woodson Ridge Farms and to Brown Family Dairy, another farm with a literary connection: owner Billy Ray Brown is the son of the late Larry Brown, who grew up in Oxford, briefly attended Ole Miss and achieved national acclaim for his novels, essays and short stories.

“Oxford lends itself really well to this because we do have a lot of local food sources, and a local dairy, farmers’ markets and restaurants with locally sourced food,” Cooley said. “When we do these field trips, we’re taking them to see these places for experiential learning.

“They’re reading about CSAs, they’re reading about certified organic, or even feedlots, and then they get to see grass-fed cattle. When I created the class, I was interested in the idea of sustainability, the relationship between food and the environment, and how they’re dependent on one another.”

Southern Cultural History

Over the course of the semester, the freshmen in Jimmy Thomas’s “Writing Southern Cultural History” course delve into underexplored topics in Southern culture, such as the commodification of voodoo in New Orleans or controversies surrounding Monsanto. But on a sunny spring day, as part of a class visit to the J.D. Williams Library’s Archives and Special Collections room, they got a crash course in conducting primary research.

Students in Jimmy Thomas’ LIBA 102 class get an up-close look at rare documents, photos and other resources at the J.D. Williams Library’s Department of Archives and Special Collections. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services.

“Has anyone ever been up here?” Thomas asked.

“Once, by accident,” a student replied, and the room erupted in laughter.

Thomas, associate director for publications in the university’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture, has taught the course for 11 years. A UM alumnus, Thomas spent several years living and working in New York before returning to Oxford as managing editor for the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, a 24-volume series.

Besides editing the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, Thomas is an editor of the online Mississippi Encyclopedia and oversees other center publications, including the online journal Study of the South.

Employing the interdisciplinary nature of Southern studies as the basis for the curriculum, Thomas weaves together a program of study that allows students to choose scholarship in a variety of disciplines. He begins by asking students to define what and where the South “is.”

Next, students choose a research focus, often using the New Encyclopedia as the basis for their initial search. Students research a wide array of topics, including the history of the university, civil rights, Southern culinary traditions or forgotten Southern authors.

“Their final, long research paper is to go out and find a story that needs to be told,” Thomas said. “We’re teaching them not just how to write, but how to think about the world in new ways.

“Our job is much different than someone instructing a large lecture class. We see our students figuring out how to write and to think.”

Faith Chatten, a sophomore, took Thomas’s LIBA class in fall 2018 and wrote her final research essay about the parallel between New Orleans voodoo and the Salem witch trials. A Colorado native, she enjoyed exploring a new subject area.

“I had never been to the South before coming to college,” Chatten said. “The class taught me a lot in my first semester of college about a culture that I had never experienced before. In high school, it was a struggle for me to just write three pages, and now three pages feels like nothing.”

Gender’s a Drag

Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy – the girls of Louisa May Alcott’s famous “Little Women” and its sequels – might seem a surprising connection to a class called “Gender’s a Drag: Gender Performance in American Culture and Pop Culture.”

UM students study gender, drag and American pop culture in instructor Colleen Thorndike’s seminar. Photo by Robert Jordan/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

For instructor Colleen Thorndike, though, a dissertation on gender performance in American novels was a gateway to developing the course, in which students study texts as diverse as Katie Couric’s “Gender Revolution” documentary and “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” a TV show hosted by the legendary drag queen.

In the course, Thorndike uses inquiry-based discussions to have students examine what gender is – and ultimately, how it’s performed. Students explore the concept of gender existing on a spectrum and discuss what it means to be transgender, cisgender or nonbinary.

“We talk about stereotypes and gender tropes, and they’re exploring a gender trope over decades to see how it’s changed,” Thorndike said. “During the drag unit, we talk about ‘performing gender’ and watch drag performances.

“Students are interested in the gender spectrum and gender issues. We talk about sexual harassments, assault and toxic masculinity. We’ve even tried to define what ‘toxic femininity’ would be – is that even a thing? They said the 1950s housewife stereotype might be that: a woman who can’t do anything for herself.”

Carlee Grace Simmons, a sophomore English major who took Thorndike’s class in spring 2019, said the texts, documentaries, class lectures and discussions opened her mind to new concepts.

“This class really helped me as a person, because it gave me new ways to understand people, and made me realize how gender plays roles in our lives, more than just physically,” Simmons said.

It’s in the things we buy, how we act and a lot of other places that I didn’t realize before the class.”

Writing about True Crime

UM alumnus Bill Boyle grew up in Brooklyn, New York, in a neighborhood famed as the setting of many mobster crime legends. As a boy, Boyle was intrigued by the tales he overheard, a fascination that has powered a prolific literary career and served as the inspiration for his LIBA 102 course, “Writing about True Crime.”

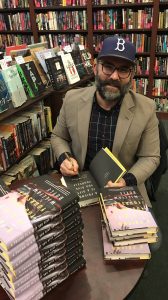

UM alumnus and instructor Bill Boyle signs book copies following a reading at The Mysterious Bookshop in New York. Photo by Charles Perry

He has authored three novels and a short story collection. While writing fiction is a natural gift for Boyle, part of his intrigue with the true crime genre comes from grappling with why writers approach the topic – and how.

“One of the things we talk about a lot in the class is the motivation behind true crime writing,” Boyle said. “It’s a hazy place. How do you treat trauma and tragedy as entertainment? That’s one of the things I’m fascinated with and try to bring into the class.

“True crime is real-world research, as opposed to just library research. People get interested in the idea that you can look at records and follow a trail somewhere.”

Martha McCaffery, a junior classics major, selected Boyle’s class because she was drawn to the topic. Her research paper, on false confessions, explored a documentary series about two boys in Canada accused of murdering a family.

McCaffery said the class overhauled her composition skills.

“I learned how to be organized,” she said. “That was one thing I’d struggled with when it came to writing papers. In high school, I followed a formula, a structure. In my LIBA class, I learned how to draw everything together and make it concise and focused.

“I never would have thought this class would have been offered, because it was so out-there. We all came to class with a shared interest, and so I found the discussion more invigorating and vibrant.”