Two UM biology professors are using a National Science Foundation award to research co-invasions of plantation trees, such as pines, with symbiotic root fungi and their mushrooms. In Brazil, pines have invaded the tropical savanna Cerrado, crowding out the natural vegetation pictured here. Photo by Stephen Brewer/UM Department of Biology

OXFORD, Miss. – Two University of Mississippi biology professors are using a National Science Foundation award to expand their research into the phenomena of co-invasions between plants and fungi.

The National Science Foundation project is focused on how plants and fungi ease each other’s invasions of non-native habitats and hopes to better understand the consequences of these co-invasions on biodiversity and on the services ecosystems provide to humans.

Invasive species are damaging to agriculture, forestry and natural ecosystem services in the U.S. and around the world, but, while co-invasions are widespread, they are under-studied.

“It is widely recognized now that species introduced from one part of the world to another can sometimes become invasive and have major consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem services,” said UM professor Jason Hoeksema, who is studying the phenomena along with professor Stephen Brewer.

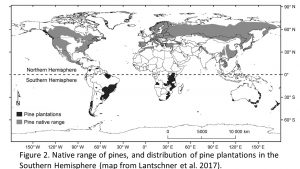

“However, most of the research on such invasions has focused on plants or animals invading solo. A primary example on which our project will focus is the co-invasion of plantation trees, such as pines, with symbiotic root fungi and their mushrooms.”

Invasive species can harm the biodiversity and functioning of ecosystems, causing native biodiversity losses and altering processes such as nutrient cycling and carbon storage. With co-invasions and their significant effects becoming widespread, researchers need a better understanding of how they work, particularly their potential progress via unique dynamics.

“Growth rates of pines introduced to the Southern Hemisphere appear to be greatly enhanced by co-invasion with mycorrhizal fungi, many of which have also been introduced to the Southern Hemisphere,” Brewer said. “The destructive competitive advantage of invasive pines over native vegetation in the Southern Hemisphere may in part be the result of ‘collusion’ with non-native root fungi.

“Understanding relationships between pines and mycorrhizal fungi is crucial to efforts to manage non-native, invasive pines and reduce their impacts on biodiversity.”

Beyond conducting novel research in this field, the professors’ project also includes training a new generation of scientists who have expertise in biological invasions, including plant-fungal co-invasions.

“These phenomena are inherently international in scope, so these scientists will need to know how to conduct collaborative research with foreign scientists across international boundaries,” said Hoeksema, who joined the faculty in 2006.

“To conduct this training, we will organize and sponsor two separate three-week courses for American graduate students, which will take place in Australia and South Africa, respectively. These courses will be conducted at world-class research institutes in those countries, and will be taught by teams of experts from the U.S., the host countries and elsewhere.”

This new cadre of scientists will include researchers from broad backgrounds that reflect the diversity of the U.S., Hoeksema said.

“Such diversity is essential for the health and vigor of any field of science, ensuring a diversity of ideas, perspectives and approaches,” he said. “Recruitment of students to our program will include the University of Mississippi, but we will also conduct regional and national searches for the best students, including via new partnerships with graduate programs at historically Black colleges and universities in our state.”

This map shows the native range of pines and the distribution of pine plantations. It was created by Maria Victoria Lantschner, Thomas H. Atkinson, Juan C. Corley and Andrew M. Liebhold for their 2017 Ecological Applications journal paper ‘Predicting North American Scolytinae Invasions in the Southern Hemisphere.’ Submitted photo

At least 20 American graduate students will receive training in the field of international invasion biology through the NSF award, providing a foundation for them to research and solve invasive species problems around the world. The trainees also will conduct outreach in high schools nationwide, teaching young students about relevant invasive species phenomena in their local environments.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has paused aspects of the outreach program, such as the international graduate courses, the two professors expect to move forward with their plans once it is viable and safe again.

When international travel safely resumes, one big question the professors will attempt to answer is what role does genomic evolution play in the dynamics of invasions and co-invasions. Searching for answers to that question will be the focus of a course at the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute at the University of Pretoria in South Africa.

“Rapid evolution, during the timespan of only decades, is increasingly recognized as common and influential, and we want to understand how it may be changing the functional traits of invasive species,” Hoeksema said.

“For example, do invasive pine trees and their symbiotic mushrooms rapidly adapt to the novel soils, enemy species and potential partner species they encounter in foreign environments? How important is this evolution for the consequences of these invasions?

“The students in our South Africa course will be trained in cutting-edge genomic analysis methods that will allow them to answer such questions.”

A course at the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at Western Sydney University in Australia will focus on answering how invasions and co-invasions feedback with global environmental change and extreme climatic events, Hoeksema said.

“For example, do biological invasions exacerbate the effects of prolonged droughts and fire on landscapes, and do those extreme climatic events promote further biological invasions?” he said. “The students in our Australian course will learn a diversity of tools for tackling these complex questions, including experimental approaches and mathematical modeling.”

Brewer first became interested in invasive species two decades ago while studying plant competition and biodiversity in highly diverse longleaf pine savanna ecosystems in the Southeastern U.S. When a non-native plant from Asia called cogongrass began invading some of his field sites, his interests shifted.

Various studies around 2000 had concluded that diverse native communities could resist invasions, as long as logging, fire and soil disturbances were kept to a minimum. But cogongrass proved to be an exception.

“Although this species thrives on disturbance, I found that it could also invade highly diverse, undisturbed pine savannas and displace three-fourths of the native plant species,” said Brewer, who joined the Ole Miss faculty in 1996. “From that point on, I became interested in understanding what gives the worst invasive species their competitive advantage over native species.”

Hoeksema’s research interest in co-invasions was sparked as an undergraduate, when he learned about plant ecology. He was particularly interested in plant interactions with symbiotic root fungi called mycorrhizal fungi because these fungi are found nearly everywhere and have potential to transform the understanding of how plants interact with the world.

He first focused on native populations of these species in North America before also studying the pines and their mushrooms in the Southern Hemisphere, where they have been widely transported and sometimes are very invasive.

“Interestingly, these introductions happen a bit differently wherever they occur, involving different subsets of plant and fungal species placed into different kinds of unique environments,” Hoeksema said. “It struck me that these diverse transplantations are a type of ‘natural experiment’ where we can investigate the ecological consequences and evolutionary dynamics of different fungal species and plant-fungal combinations.”

Beyond working with research partners in South Africa and Australia, the two professors also have ongoing collaborations with scientists in Brazil, Argentina and Europe.

Hoeksema is the principal investigator with Brewer as the co-principal investigator on the NSF award, which is No. 1953299 and titled “Dynamics, Consequences, and Management of Plant-Fungal Co-invasions.” Funded for $274,867, the award has an estimated end date of May 31, 2022.