Eric Peters works the line at Grit restaurant in Taylor. The University of Mississippi student, who battled alcohol addiction during his career as an executive chef, has been sober for years and is working on his degree. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

OXFORD, Miss. – A successful chef and father of two used to drink vodka at 6 a.m. until he passed out in public, then wake up and try to go to work and conceal his problem.

A bright, young student hooked on alcohol and Xanax accumulated multiple arrests in 18 months, including one for assaulting a police officer. He eventually landed in prison for 90 days.

A gifted young man went to a major university on scholarship but partied his way out of school twice. He spent several blurry years lost in a cycle of arrests, serious depression, liquor, pills and drugs.

These individuals – Eric Peters, Sam Peeler and Weston Aron – all have one thing in common. They’re University of Mississippi students who have overcome serious substance abuse that could have killed them, and each of them are on track to earn their degrees.

They haven’t changed their lives alone. They chalk a lot of their success up to the support of UM Collegiate Recovery Community, a part of the new William Magee Center for Wellness Education. The CRC is a network created for students to help them draw support and accountability from one other to stay on track.

Erin Cromeans, UM assistant director of wellness education, oversees the CRC. She has seen how this community provides students a vital link to the support network of other students in recovery.

“It is important for students to connect early and engage often, all while navigating college life,” Cromeans said. “Our CRC continues to grow not only in membership size, but in opportunities for social activities, campus leadership and engagement, and also scholarship. I’m excited for the continued momentum of our organization.”

CRC provides a variety of resources to students, as listed on its website. The University Counseling Center also hosts a Recovery Support Group, which meets year-round every Tuesday from 11:30 a.m. to 1 pm. in Lester Hall. It also offers a support group for loved ones and children of alcoholics and addicts during the school year.

CRC students speak with brutal honesty about their addiction, low points and recovery. They inspire one another to keep going. Their stories also offer hope for those who are considering entering treatment while continuing their studies.

Peters, Aron and Peeler wanted to share their harrowing stories and inspiring paths to recovery in hopes of convincing others to get into treatment and find support for overcoming their addictions. They also want to raise awareness about the university’s support system.

Not even one drink

Peters works within reach of a bottle of rum that flavors up the dishes he cooks at Grit, a trendy restaurant in Taylor. But he knows if he took one sip while no one was looking, it would undo more than 1,300 days of sobriety. The prospect of that terrifies him.

Peters, a 39-year-old junior, is making good grades and forging a path into his future. He wants to help those who are going through what he’s been through.

“I want to understand why it happens, and if there is a way we can figure out the breaking points,” Peters said. “I want to know if we can identify those behaviors and modify them.”

A serious alcohol problem caused Peters to lose lucrative jobs as an executive chef and later at an automotive plant, ended his marriage and strained relationships with loved ones. With relapses into alcoholism behind him, Peters is on the right path, but it hasn’t been easy, not by any stretch of the imagination.

“The memory of what happens if I take one drink keeps me sober,” Peters said, tearfully. “That’s pretty scary. Having that memory helps me. That relapse and what happens leaves no room for error for me.”

He’s leaned heavily on the campus CRC, drawing both support and accountability from other students who are trying to stay on track. Peters credits the support of CRC as crucial to his recovery.

“If you think you have a problem, you probably do and it doesn’t have to get to a point where you can’t stop,” Peters said. “Alcoholics do a lot of isolating. At a certain point, people you normally hang around with don’t want to hang around you.

“Your family will also be on you, and you have to get away from them. You need to know you are not alone. It’s a really good feeling when you realize that.”

Peters stands outside the George Peabody Building, where the majority of his classes are offered. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

Dark times

The story of Peters’ substance abuse starts in the kitchen. In culinary school, he immersed himself in the culture, and drugs and drinking were a major part. He was good at the work, though, and started cooking in fine dining restaurants in Dallas, making $70,000 a year as an executive chef.

It was a high-pressure job, and vodka became his crutch. He’d stash bottles of it along his route to the station where he would catch the train to work every day.

“I got drunk taking the train to and from work,” Peters said. “I got drunk at 6 a.m. and I passed out on the train. I barely woke up in time for my stop.

“I was just unhappy with life and couldn’t deal with anything, especially with the drinking, which just made everything worse.”

From there, things got really dark for Peters. He was drinking all the time. Going through multiple fifths a day isn’t conducive to holding down a job, especially for someone leading a team. It’s also not helpful when you’re a husband and father.

He and his wife had a son before moving to her hometown of Jackson. She became pregnant with a second son, born 16 months after the first. Meanwhile, Peters kept on drinking. They moved back to Dallas, but he kept drinking there, too.

His wife left him, took their sons and returned to Mississippi. Peters moved back to his native Kansas and lived in his parents’ basement. He kept on drinking. Though he was there only six months, he lost four different chef gigs after his bosses asked about his alcohol problem.

“So, the heat is turning up a little bit,” Peters said. “I decided to move to New Albany, where my wife and boys were to try put my family back together. That lasted about a month. Then I moved into Haven House in 2014.”

Peters’ first attempt to get clean at Haven House didn’t take, despite spending 90 days in a treatment program. He stayed sober for about six months, moved back in with his wife and got a job inspecting cars for water leaks.

One beer, cracked open on a whim, undid all his progress. The next day, a bottle of vodka in hand, he slid back into the drinking life again.

Down in detox

His wife kicked him out again. He moved into an apartment, where he drank for two solid months until he called his dad one day to ask for a ride to the emergency room. Peters wanted to get clean, but he was afraid to stop drinking because he had a seizure on one previous detox attempt.

This time, he spent a week in detox. He found himself in a facility with some people who suffered serious mental health issues. The experience shook him up, so he got out his Alcoholics Anonymous books to pass the time and take his mind off his surroundings.

“There, I figured out that I couldn’t do it my way and make sobriety work,” Peters said. “I didn’t do what I was supposed to do the first time. I wasn’t honest about everything.”

A path into the future

These days, he’s honest about his past and optimistic about the future. He spends time with his sons, who are 7 and 6. He works at Grit. He got engaged to a co-worker who is also in recovery and studying nursing. They married June 22, his 1,301st sober day.

“We go to meetings together,” Peters said. “We share a lot of very similar interests. It’s not just that we both have had admittedly checkered pasts. I don’t want to say that. We just fit together. It’s a great feeling.”

He also fits right into the CRC’s community of those in recovery and found solace in knowing he is not alone. This keeps him going, along with the memory of the consequences of taking that first drink.

At Grit, he sometimes closes the restaurant alone. He walks alone past the fully stocked bar, and he isn’t tempted to take a sip there, even though it’s unlikely anyone would know. He knows he could only hide it for so long before the descent into alcoholism would start.

He doesn’t want to throw away the future he’s carved out for himself, thanks to the CRC, and the chance to earn a degree from the university.

“I’m really grateful for all the opportunities Ole Miss has given me,” Peters said. “It’s amazing to think about what I had been doing and to realize that I’m still around.”

Sam Peeler, who used to begin every day at 10 a.m. by drinking and taking Xanax, eventually wound up in prison. He is sober and working on his degree at the University of Mississippi, thanks to the support network of the university’s Collegiate Recovery Community. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

Spending ‘every dollar on Xanax’

Peeler was an Ole Miss freshman who began every day at 10 a.m. by drinking, taking Xanax bars and smoking marijuana.

“I was spending every dollar I could find on Xanax and drinking from 10 a.m. until I passed out, and I would wake back up and start drinking again until I passed out again,” Peeler said.

He couldn’t keep from getting arrested in Oxford with multiple felonies on his record, including four public intoxication charges, burglaries, simple assault and also assault on a police officer. He was arrested seven times between 2015 and 2017. He missed 31 days of class in a semester.

His dependence on Xanax started when he was in high school.

“I had a really bad problem,” Peeler said. “I would text stuff. I would put stuff on social media. I would ruin relationships with people. I sent some of the meanest stuff out there to everybody and I’d wake up, and be like, ‘hmm.’

“I’d take another Xanax bar to forget about it.”

An addicts’ system

Peeler said he hit bottom while going through the drug court program, being randomly drug tested as part of his probation. He Googled ways that he could drink a six-pack of beer and still pass his screenings. His research led to a complicated, intense regimen that worked for him, but only for a while.

If he drank a six-pack, he’d have to run 4 miles the same day, run 4 miles the next morning, spend an hour in a sauna or steam room, eat a certain amount of protein and down two pots of coffee within an hour of providing a sample. It was tricky because he never knew when he was going to be called in for a test.

This cycle continued for a few months until he had an epiphany.

“I went through all that Google process and the research and had to learn all of that just to try to drink a six-pack,” Peeler said. “That’s when it hit me that I was an addict.”

But learning you’re an addict isn’t always enough to get someone into recovery. Peeler kept going, even though the screenings gave him anxiety to the point he would throw up before giving his sample. He kept hoping he could keep this up.

One day, he got the call he’d failed: he tested positive for marijuana. He contends he wasn’t smoking it, but was hanging out with people who were. Drug court sent him to jail for 10 days.

“That’s when it hit me that my people, places and things needed to change,” Peeler said.

‘The worst of the worst’

He didn’t learn his lesson, though. Addicts can be a stubborn group.

Peeler tested positive and violated probation for the second time. He was sent to the Lafayette County Detention Center for three weeks without any idea of when he was going to be released. When the three weeks passed, he was sent to the Delta Correctional Facility for 90 days.

It took this scenario for him to get serious about getting his life in order. Prison offered him time to reflect and plot a course of action.

“I sat in there, and that was where I realized this is where the worst of the worst come,” Peeler said. “This is a doghouse. Right there, I started writing a journal every day about how I am going to change my life.

“I started reading the Bible and realizing that when I get out of here, my life needs to change. I couldn’t keep doing all these same things and hurting the same people.”

His redemption story began there. He went back to school. He even started showing up for class and going to the library – lower case, library – not the local bar of the same name. And Peeler, a product of a wealthy family who never really held a job before, was working and paying off his debts.

He was also hitting the gym instead of the bar.

Peeler says he draws strength from those in the CRC group. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

“I got everything squared away with drug court so I could start traveling out of state,” Peeler said. “All that productivity truly helped me. That’s when I started realizing where I am.

“This is the healthiest I have ever been. That’s when I realized it was time for me to start living this way.”

Finding community with CRC

He also found his home within the CRC, and draws strength from those in the group.

“I love these people,” Peeler said, calling them a major part of the reason he’s been sober two years and three months.

He’s also taken a long look at who he lets into his life and has replaced some of the more negative influences with more supportive, understanding friends around him. But he does see those “night on the town” stories on Snapchat sometimes, which makes him feel like he’s missing out.

Still, his friends find good times for him that don’t involve booze or pills.

“The friend group I have now is very toned-down,” Peeler said. “They’ll still have a beer with dinner, or go out to the bars on the weekends, but they never suggest to go have a beer and let me drive them around. They always have clean and sober fun.

“I’m at a peak in my life. I’m happier now and soberer than I’ve ever been.”

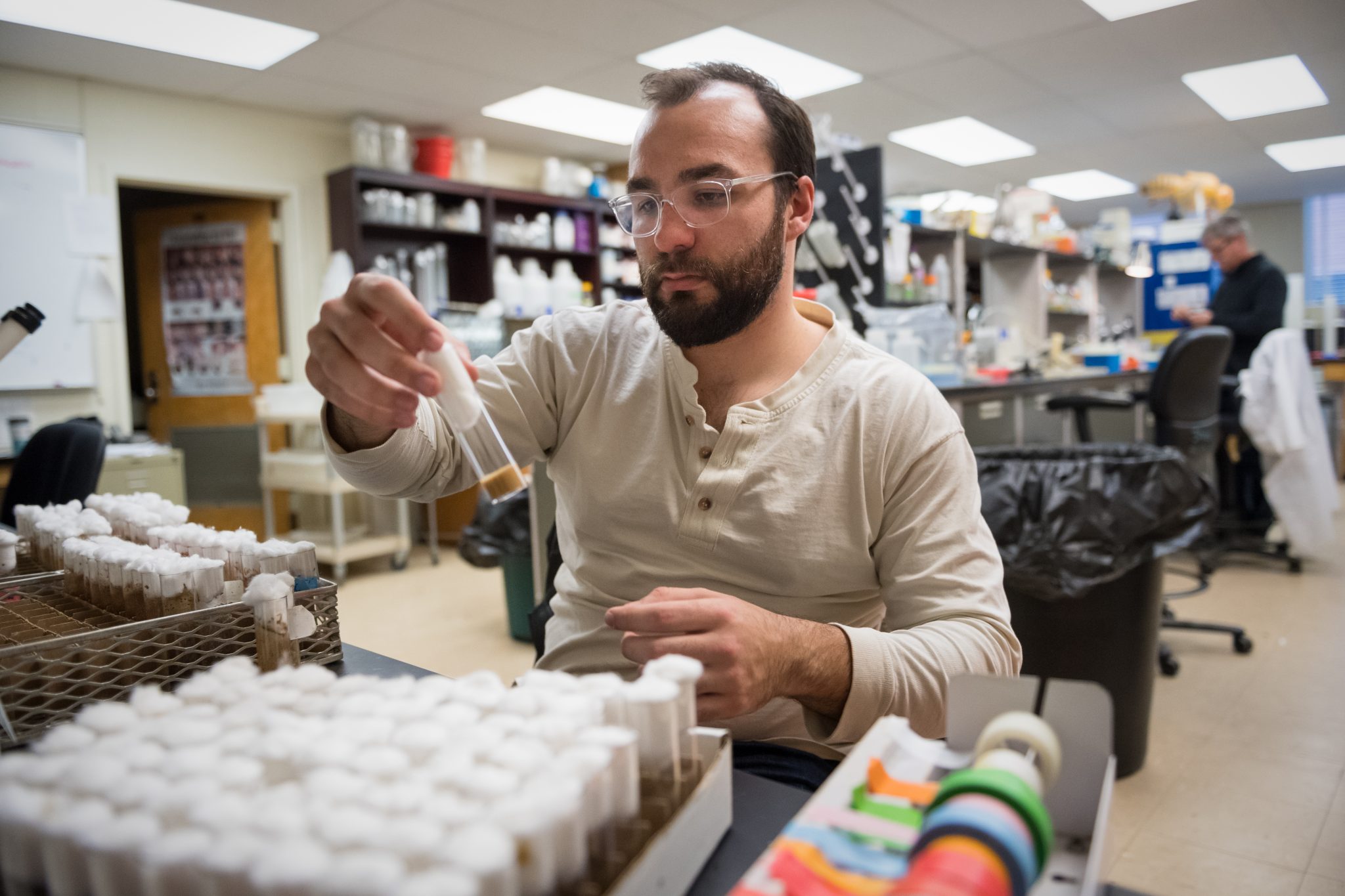

Weston Aron works in a University of Mississippi biology lab feeding cloned fruit flies. Aron, whose promising academic career at a major university was derailed by drugs, alcohol and arrests, is sober and working hard on his degree at Ole Miss. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

‘Terminal uniqueness’

Aron started his academic career on scholarship at a major university, but his time there was rocky and brief.

One night during his first semester, he was heavily under the influence of Xanax when he called all his family members and told them he was going to kill himself. He awoke to police in his dorm room but had no memory of what happened.

A week before finals, he was arrested for another incident.

“Because I was arrested, I didn’t show up to any of my finals,” Aron said. “Honestly, I probably wouldn’t have gone anyway.”

After the arrest, he left and spent two years out of college, working in the insurance industry. He went to Itawamba Community College online, then got a job making decent money, which probably would have allowed him to pay for school without debt.

He enrolled at Ole Miss in spring 2015 as a philosophy major after the two-year period of working and not taking classes was through.

He worked over the summer and saved enough to cover a semester of tuition and other costs.

“I blew it all in one weekend for my 21st birthday, not intending to do it,” Aron said. “I got blackout drunk and then got back home and checked my bank account. There are several thousand dollars I have no accounting for.”

A blur

His college experience was a blur of alcohol, marijuana and pills, such as Xanax and the ADHD medication Vyvanse. Winters were particularly hard on his emotional state. His depression worsens during the cold months, though he hasn’t actually been diagnosed with seasonal affective disorder, he said.

The Vyvanse raised his spirits, as it’s a strong stimulant, but when he came off it, things would get rough.

“It is like four to five days of immeasurable sadness, and you have nothing you can do to fix it,” Aron said. “You drink or get high to fix it, but really you are just super-tired. Every bit of serotonin or dopamine in your brain is just depleted, and so you can’t fix that and that goes on until spring.”

Cumberland Heights

In the spring of 2016, Aron was at his low point. He finally listened to the people around him and decided to leave Oxford and enter rehab at Cumberland Heights, just outside Nashville.

“I left town and I took pretty much all of the advice that was given to me,” Aron said. “I was really, really desperate when I left here. They told me about the cliche of new playground, new friends being important in recovery. I took that to heart.”

He wanted to finish his bachelor’s degree but was reluctant to return to Oxford. He was only familiar with the nightlife, after having spent lots of his time either working in bars or patronizing them.

His grandmother, who works as a counselor, found a resource for him that would become invaluable. She gave him information on the CRC. Aron followed up with Cromeans to make sure the support would be what he needed before he decided to re-enroll at Ole Miss.

These days, he’s an education major and finding ample help in CRC.

“It has been invaluable, for one because I have a lot more nontraditional students in the CRC,” Aron said. “A lot of them are people who have obligations outside of class, or all of their obligations are in class.

“I’m taking 18 hours, not because I’m just an overachiever or because I’m obsessive, like most addicts are, but I have to do it to graduate on time.”

Finding normal

Aron has learned a term that is important to him: “terminal uniqueness.” It refers to the false belief many addicts have that their experience is unique to themselves and that any other addict won’t be able to relate to them. This keeps many out of recovery because they think they’re alone.

“You make yourself think that it had nothing to do with the drugs and the alcohol because even six months later when I am clean and sober, I am still thinking about killing myself all of the time,” Aron said. “When you start drinking and smoking pot at 13 and eight years later, you go for the first time since you were 16 for just three days without using, your brain is still messed up.”

He’s found it important to be involved in student organizations that give a lot in return for his time. Those groups have to serve his needs as someone in recovery.

“Every time I come to a CRC meeting, or event, it helps me as a recovering alcoholic because I feel like I am giving back to other addicts and alcoholics, which is one of the tenets of any 12-step program, or any recovery program,” Aron said.

“It’s going to take a couple of years to get back to normal. That’s what I am in right now, but I’m so hopeful about my future.”