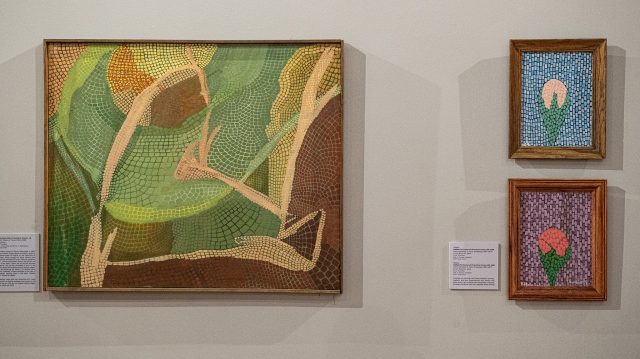

Works by Theora Hamblett (right) and her friend Ruthie Marie Smith Noyes hang together in the new ‘Friends of Theora’ exhibit at the University of Mississippi Museum. The exhibit seeks to show the influences surrounding and inspiring the work of Hamblett, who was long considered a self-taught artist. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

OXFORD, Miss. – Think of Theora Hamblett and you’ll likely see bright, multicolored trees from a bird’s eye view, or maybe a self-taught spinster whose visions inspired her to create art that would hang in the Museum of Modern Art.

But that’s not all Hamblett was.

A new University of Mississippi Museum exhibit, “Friends of Theora,” shows not only her kaleidoscopic trees, but the formative work and the inspiration she drew from the art community in Oxford. The exhibit runs throughout 2023. The museum is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays.

The new University of Mississippi Museum exhibit ‘Friends of Theora’ strives to show the formative work and inspiration the famous painter drew from the arts community in Oxford. The exhibit is on display through the end of 2023. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

“People think of Theora as self-taught, as a loner, a spinster, but she was actually a part of this vibrant community of artists,” said Melanie Antonelli, curator and collections manager at the UM Museum.

“I was frustrated with the oversimplification of her story. People minimize who she was because that’s easy. I’m interested in the multifaceted Theora who was a part of her community.”

Following Hamblett’s death in March 1977 at age 82, more than 800 of her paintings and drawings were left to the university, giving the UM Museum the largest collection of Hamblett’s work. Among these paintings are many works that were not created by the famous artist, Antonelli said.

“It’s a tradition among artists to trade or give your art to other artists,” she said. “A lot of these works belonged to Theora and were actually gifted to her by artist friends.”

Some of these pieces had been misidentified as Hamblett’s work but were actually created by friends in the arts community, Antonelli said. Among them are similar illustrations, such as Ruthie Marie Smith Noyes’ paintings of bright, semi-pointillist trees on a cloudy background. Noyes, wife of former Ole Miss professor and vice chancellor Charles Noyes, likely took inspiration from the artist’s work.

Theora Hamblett’s work in ‘The Little Red Shoe’ (bottom) is tonally similar to the work of Malcolm Norwood, an artist and professor at Delta State University, which hangs above it. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

The exhibit includes rare examples of Hamblett’s observational still-life painting and drawings, a standard practice by any trained artist. Hamblett, commonly considered a self-taught artist, took art classes at night at the university, and many of her paintings show influence from trained artists, Antonelli said.

Some works appear to be experimental and suggest the influence of other artists, including the instance of “The Little Red Shoe,” wherein a beige and tan background of various hues give way to a small red-and-white high-top sneaker. The color scheme and tonality are similar to the painting that hangs directly above it, though the artists are not the same.

“What I love about this exhibit is, at a glance, you won’t be able to tell what’s Theora’s and what isn’t,” she said. “This shows, I think, that she took great influence and inspiration from the artists around her.”

The first work displayed in the collection is a painting of a fallen tree created in 1950, in the earliest years of Hamblett’s art career and before her paintings became internationally renowned.

The dark colors and lack of contrast hardly fit what one might imagine Hamblett would ever paint. On the gray bark of the fallen tree, however, there is the repetition of shape and color that would soon become her calling card.

“This exhibit, I think, shows Theora was a person,” Antonelli said. “She worked and honed her craft. If you really love Theora, you should see all of Theora – as an artist and a person.”