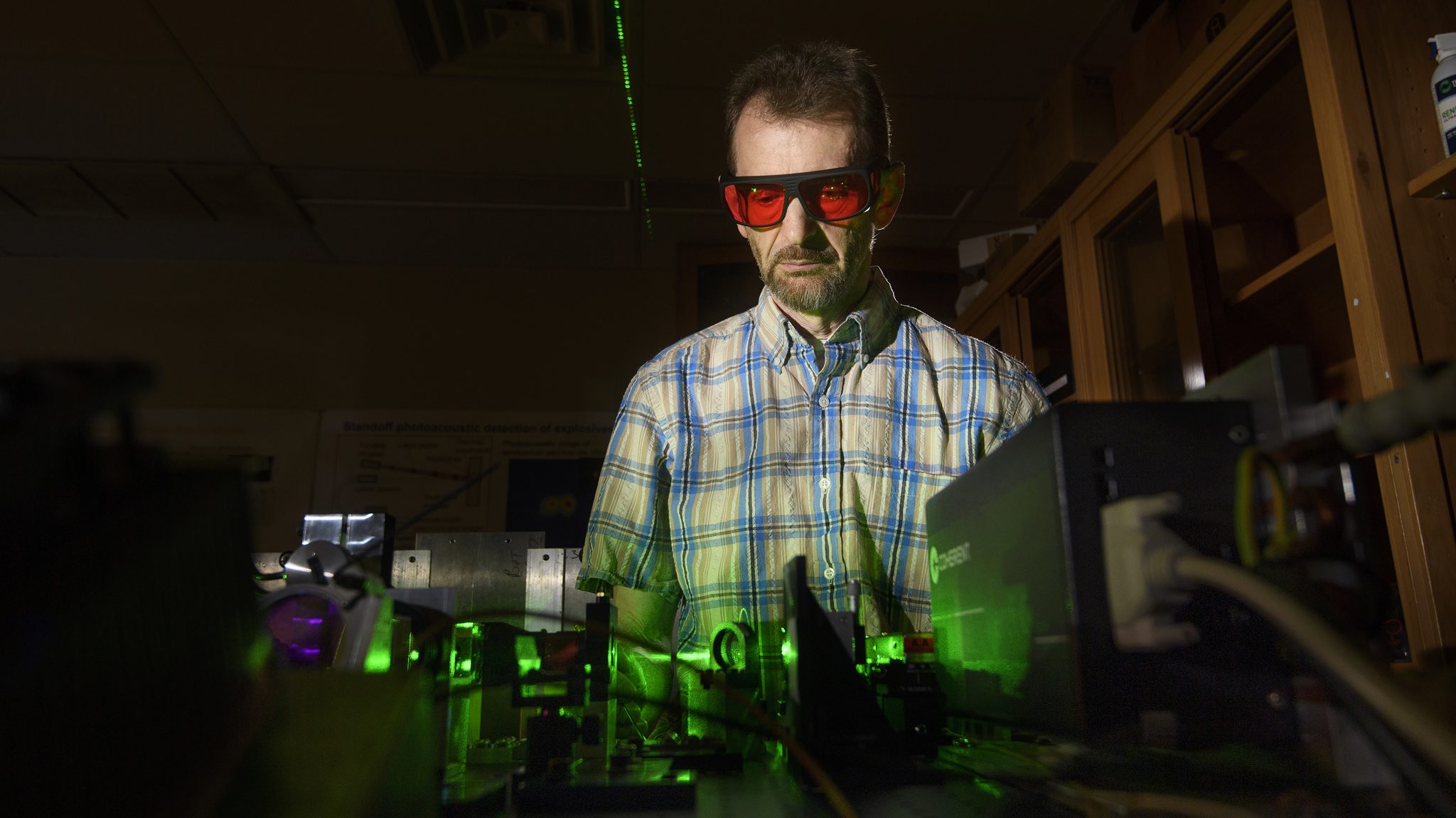

UM researcher Vyacheslav ‘Slava’ Aranchuk demonstrates the Laser Multi-Beam Differential Interferometric Sensor system in his lab at the National Center for Physical Acoustics. Aranchuk has been issued a U.S. patent for the technology, which shows promise for locating buried landmines as well as a variety of nondestructive testing applications in noisy environments. Photo by Thomas Graning/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

OXFORD, Miss. – Buried around the world are millions of landmines – never sleeping and silently waiting for victims.

The removal of landmines – both anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines – is a slow, labor-intensive task, often done by humans on their hands and knees, but a University of Mississippi researcher is developing technology that could greatly speed up the process.

The new device is a laser-based sensor developed by Vyacheslav “Slava” Aranchuk at the university’s National Center for Physical Acoustics. Mounted to a moving vehicle, the Laser Multi-Beam Differential Interferometric Sensor, or LAMBDIS, can detect buried objects such as landmines much quicker – an improvement over current technologies.

“The lingering scourge of landmines presents a serious challenge to rapid and accurate interrogation of large areas from moving vehicles,” said Aranchuk, a principal scientist at the NCPA who came to Ole Miss in 2008. “LAMBDIS allows measurements from a moving vehicle. This feature will speed up the detection of buried objects.”

Aranchuk was issued a patent Oct. 1 for the device, which also presents several market opportunities for nondestructive testing applications in noisy environments.

In 2017, landmines and explosive remnants of war caused 7,239 casualties, including 2,793 deaths, according to Landmine Monitor 2018, an annual report from the Nobel Prize-winning International Campaign to Ban Landmines. Civilians accounted for 87 percent of these casualties where the status was known, and children constituted nearly half, 47 percent, of all civilian casualties where the age was known.

Hundreds of victims go unreported, especially in countries experiencing conflict, such as Afghanistan and Syria, the two leading counties by casualties in 2017.

Existing laser vibration sensors can’t be operated from moving vehicles because of their sensitivity to the vehicle’s motion and environmental vibrations. The LAMBDIS functions while being far less sensitive to motion.

The sensor’s array of 30 laser beams is directed at the area that is being searched, and the light reflected from different points on the ground is combined in a way that provides low sensitivity to the motion of the sensor.

“LAMBDIS provides a measurement of vibration fields with high sensitivity while having low sensitivity to the whole-body motion of the object, or the sensor itself, allowing for operation from a moving vehicle,” Aranchuk said.

Vyacheslav ‘Slava’ Aranchuk shows off the Laser Multi-Beam Differential Interferometric Sensor system in his lab at the National Center for Physical Acoustics. Photo by Thomas Graning/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

In laboratory and field tests, LAMBDIS detected buried objects 25 feet to 65 feet away from a vehicle traveling about 8.5 mph. Aranchuk expects both the speed and distance of detection to improve as the device is refined.

“The next step in the research is to increase the number of points on the ground that could be simultaneously measured and to develop methods to increase the speed of detection,” he said.

Aranchuk, who started on the project in 2013, presented his research recently at The Optical Society’s Laser Congress in Vienna.

Beyond detecting buried objects, market opportunities for LAMBDIS include nondestructive testing, damage and corrosion detection, assessing bridge and structure integrity, noise source identification, inspecting automobile and aircraft components, full-field vibration analysis, and measuring dynamic strain and stress.

“We are thrilled and proud of the progress Dr. Aranchuk and his team at NCPA have made on the difficult and important problem of rapid landmine and buried object detection,” said Josh Gladden, UM vice chancellor for research and sponsored programs. “LAMBDIS is an enabling core technology that has applications in many nondestructive testing applications where structural assessments need to be made in difficult environments and a great example of UM research helping solve real problems.”

Aranchuk’s research is sponsored by the U.S. Department of the Navy’s Office of Naval Research under awards No. N00014-13-1-0868, N0014-15-1-2660 and N00014-18-2489.