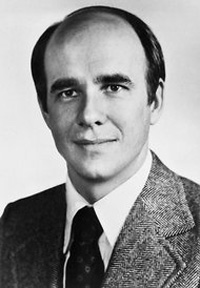

Thomas K. McCraw, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian who used biography to explore thorny issues in economics, died on Saturday in Cambridge, Mass. He was 72.

Mr. McCraw earned a master’s degree and doctorate in history from the University of Wisconsin and taught at the University of Texas before moving to Harvard.

He had been treated for heart and lung problems, his wife, Susan, said. Professor McCraw, who taught from 1976 to 2007 at Harvard Business School, won the Pulitzer for history in 1985 for “Prophets of Regulation: Charles Francis Adams, Louis D. Brandeis, James M. Landis and Alfred E. Kahn.”The book focused on those men, of different eras, to illustrate how government regulation of industry affected the American economy from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.

Professor McCraw, who taught from 1976 to 2007 at Harvard Business School, won the Pulitzer for history in 1985 for “Prophets of Regulation: Charles Francis Adams, Louis D. Brandeis, James M. Landis and Alfred E. Kahn.”The book focused on those men, of different eras, to illustrate how government regulation of industry affected the American economy from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.

Adams was president of the Union Pacific Railroad in the 1880s; Brandeis, the lawyer and Supreme Court justice, worked to curb the power of banks and corporations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; Landis was chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission during the Depression, and Kahn was chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board, which deregulated airline fares in 1978.

The book was recognized for melding scholarship and engaging prose.

“Mr. McCraw explains sophisticated economic theory in accessible terms,” The New York Times Book Review said, “and he has a historian’s knack for isolating such basic American traits as a mistrust of big business and for showing how regulators manipulated these traits to implement their policies.”

In “Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction” (2007), Professor McCraw examined capitalism through the life story of its leading 20th century advocate, with his Darwinian theory of “creative destruction”: that businesses must be rendered obsolete and extinct by other, better businesses if an economy is to move forward.

In “The Founders and Finance: How Hamilton, Gallatin and Other Immigrants Forged the American Economy,” published this year, he wrote about how a nation born into financial ruin after the Revolution saved itself and created a stable financial system. He credited the efforts of immigrants like Alexander Hamilton, born on the Caribbean island of Nevis, who was the nation’s first secretary of the Treasury, and the Swiss-born Albert Gallatin, who was the fourth Treasury secretary and whose almost-13-year tenure remains the longest in American history.

“The key feature of his work is the use of biography,” said Geoffrey G. Jones, who succeeded Professor McCraw as the Isidor Straus Professor of Business History at Harvard. “You hear about personal lives, motivations, but he manages to deal with issues, like regulation, that are usually left to dry textbooks. That was his real gift.”

Thomas Kincaid McCraw was born on Sept. 11, 1940, in Corinth, Miss., near where his father, John, a civil engineer for the Tennessee Valley Authority, was helping to build a dam. The family moved frequently, and Thomas graduated from high school in Florence, Ala.

He attended the University of Mississippi on a Navy R.O.T.C. scholarship and after graduation served four years in the Navy, mostly in Bermuda. He earned a master’s degree and doctorate in history from the University of Wisconsin and taught at the University of Texas before moving to Harvard.

Professor McCraw lived in Belmont, Mass., with his wife, the former Susan Morehead. College sweethearts at Mississippi, they married in 1962. His other survivors include a daughter, Elizabeth McCarron; a son, Thomas Jr.; a brother, John; and three grandchildren.

Professor McCraw’s other books include “American Business, 1920-2000: How It Worked” (2000), a compact overview.

At Harvard, he developed a standard first-year course for M.B.A. students, “Creating Modern Capitalism,” which enhanced the profile and popularity of business history at the school and whose syllabus became a textbook, now widely used, of the same name.

“He was a historian who made things accessible to a far wider range of people than normally read scholarly works,” Professor Jones said. “And not by trading down. The work isn’t simplistic. It’s engaged with materials in the deep sense. It’s just very accessible. That’s a very difficult thing to pull off. Very few academics can.”