OXFORD, Miss. – Calling Ole Miss football great Jim Weatherly an interesting man would be an epic understatement.

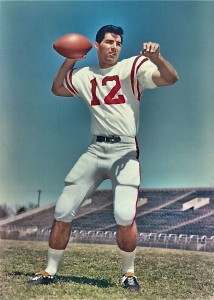

Weatherly, a native of Pontotoc, played for legendary Ole Miss Coach Johnny Vaught as an All-Southeastern Conference quarterback and honorable mention All-American on the 1964 team. He was also a member of the only unbeaten and untied national championship squad in University of Mississippi history in 1962 – a team that captured the SEC championship that year and again in 1963.

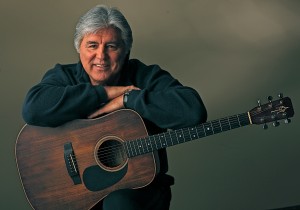

But his success hasn’t been limited to football. As a professional songwriter, he penned “Midnight Train to Georgia,” which Gladys Knight and the Pips turned into one of the biggest hits of all time. His efforts led to him being elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame in this year’s class alongside music legends Donovan and the Kinks’ front man Ray Davies, among others.

But that’s not all that’s interesting about Weatherly. As a hit songwriter, he also traveled in the same social circles with the elite of the music and acting industries when he lived in Los Angeles. His biggest hit song came from a phone conversation he had with Farrah Fawcett. In the 1970s and ’80s, he also played flag football with “The Six Million Dollar Man” Lee Majors and actors Mark Harmon and James Caan, among other notables.

Weatherly, 71, who lives in Brentwood, Tenn., with his wife, Cynthia, their daughter, Brighton, and son, Zack, recently did a phone interview with University Communications about his career, his election to the Songwriters Hall of Fame and his memories of playing for Vaught.

Here’s the full interview:

Q: Take me back to when you decided to attend Ole Miss. What drew you to this place?

A: Well, growing up, I had always been a big fan of Ole Miss football and I followed Ole Miss all through high school, even when I was in junior high and grammar school. There was just kind of a mystique about Ole Miss for me. I grew up in Pontotoc. All this was happening just 30 miles away from me when I was growing up. I used to listen to the ballgames on the radio when I was growing up. There was just this mystique about listening to what was going on just 30 miles away and in those red-and-blue uniforms.

I don’t think I ever made a conscious decision to go to Ole Miss. It was just kind of like if I ever got the opportunity that’s where I was going. It wasn’t something I really thought a lot about. It was just I wanted to be part of that mystique of that Ole Miss Rebel football team. So, it was just kind of a foregone conclusion that if I ever got the opportunity, that’s where I would go.

Q: So, what was it like to be on the campus during the time like when you’re here? I mean it was obviously a period of great football success, which you were part of, there was definitely the James Meredith enrollment and the deadly riots that happened after it – obviously a lot of tension here, but also great pride in the football team at the same time. What was it like to be an Ole Miss student-athlete sort of caught between those two worlds?

A: Well, oddly enough, I didn’t let what was going on around me affect me. I was there to go to school and get an education and to play football. So I just didn’t dwell on the stuff that was going on around me. I am and I always was a live-and-let-live kind of person and I wasn’t any kind of an activist either way. I just minded my own business and did what I was there to do.

Q: So, what are some of the memories from your time at Ole Miss that really stand out to you? What are some of the memories you cherish when you look back?

A: Well, again, you know, like I said earlier, just being there and being around what was a larger-than-life situation. I mean Ole Miss, that name, had always been in my head, and to be there and be a part of it – I was in awe of a lot of the things that were going on around me. I was in awe of being a part of that Rebel football team and being a part of the Ole Miss student section. As far as particular memories, there’s just the friends and being coached by John Vaught. Those are things that you dream about and things you never forget.

Q: What was that like to play for Johnny Vaught? He’s such a revered figure around here?

A: It was a thrill. It was an honor. He was like a rock star, and so I was in awe of him, and to find myself on the field and he was talking to me; that was a pretty big deal.

Q: Yeah, I guess so. Is there any one Johnny Vaught story that stands out to you, anything you remember?

A: You know, the thing that comes to mind about Coach Vaught is I don’t think I ever heard him raise his voice. He was kind of like a John Wayne type of character who was very quiet, very direct and didn’t have to raise his voice to get his point across. A lot of coaches feel like they have to scream and yell, and he was not that way.

The other thing about Coach Vaught, in my particular case, was, surprisingly, he was very supportive of my music. I remember my senior year, the day we reported to summer camp for the fall practice, I had a dance I was supposed to play that night, because I’ve been playing some dances with my band during the summer. And so, I can’t believe I did this, but I did. Sometimes I don’t know where I got some of the gumption that I had. I went over to Coach Vaught’s office, sat down with him and said, “Coach Vaught, I’m supposed to play a dance tonight.” Practice hadn’t started yet, but it was the day we reported. And he was just very quiet. He said, “Well, we just won’t start bed check until tomorrow night,” and that just absolutely blew me away. I couldn’t believe he was that calm, that supportive, that in tune to the realities of other people’s situations, and it always stayed with me. I respected him quite a bit, but that made me respect him even more.

Q: Do you think that that was part of why he was so great at what he did, that he had that sort of intuition, that kind of instinct?

A: Probably so. I don’t know what went down and how other people’s relationships were with him. I wasn’t as close to Coach Vaught as some of the other quarterbacks. But that was probably because I was just so in awe of him. It’s hard to me to be really close with people I’m in awe of. But for me, it was for the way he treated me. He even talked to me one time about getting me on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” I didn’t take it really seriously or anything like that, but he was serious.

Q: That was back when the Beatles and other groups were making a splash on that show, right?

A: Right. And the thing is (Vaught) knew I didn’t play music during the football season. That was something that my own code of values wouldn’t let me do. I had my guitar in my room and I played my guitar, but that was because it relaxed me. I didn’t have to go out, carouse and do things. I just played my guitar and studied.

Q: It might not be just from when you were student here, but do you have a favorite Ole Miss memory?

A: No, not one in particular. The memories are kind of jumbled up and just a major part of my life: friends that I made, my roommates. I roomed with (Ole Miss fullback George M. “Buck” Randall) one when I was there and (I remember) just being around other football players that were there for the same reason I was there, the camaraderie. I remember (assistant football coach J. W. “Wobble” Davidson) walking up and down the halls, trying to smell cigarette smoke or see if anybody was playing cards. It’s just tons of memories that you can’t nail down to a particular incident. Those are some pretty good ones.

Q: Take me back to the moment you decided that you would pass on the opportunity to play in the National Football League after having a pretty successful college career. How did that come about?

A: I never considered playing pro ball. I never considered it. I had enjoyed the college football. I just didn’t want to continue with that. When they offered me $12,000 and Joe Namath got $400,000, I thought, well, they’re not taking me too seriously, so I don’t think I should take them too seriously.

Q: Namath was first team all-SEC and you were second team, isn’t that right?

A: Right.

Q: How did you get into songwriting and then how did you find a way to make a living at it?

A: That’s a good question, especially about how to make a living. I started writing when I was really young. My grandmother used to tell me I would sit down on her front porch and make up cowboy songs, coming home from the cowboy movies on Saturdays. But I really didn’t start making up songs until Elvis came on the scene and there was the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll. I also really loved rockabilly music and really got into it. It was then at that point I started to really try to write things like what I heard on the radio.

I just did it because I could do it and it was fun. It came natural to me. It wasn’t something that was forced or I had to like really work hard at. I just continued that all my life. I wrote songs while I was at Ole Miss, but that didn’t take anything away from anything else I was doing. It was something that was so natural to me and I didn’t have any aspirations of really getting anybody to record it. It was just something I did for fun.

Then, when I left with my band to go to California in 1966 and I was writing songs for our group, I wrote songs that were on our first album and just kept on and kept on and found that some people were giving me positive feedback. Eventually, I found the one guy who said what I wanted him to say. I met a guy named Larry Gordon. He listened to about three of my songs and said, “I want you to be at my attorney’s office tomorrow morning at 9 a.m. I’m going to sign you as a writer. I promise you, I will push your songs through the sky.”

That was the commitment I had been looking for from somebody. He made me believe what he said to me. And so, I signed with him. I didn’t even have an attorney, which I wouldn’t advise people to do. Fortunately, it worked out in my favor.

Q: You mentioned to your love for rockabilly and for Elvis, but who are some of the songwriters and artists that inspired you?

A: In those days, I don’t think I was aware so much of songwriters. Otis Blackwell does come to mind, and he wrote some of the Elvis Presley songs. The person who really changed the way I thought about songwriting was Jimmy Webb. I was in Los Angeles and I’d been pitching some songs to Johnny Rivers. Johnny Rivers had just signed Jimmy Webb as a songwriter. I was aware of the song that Jimmy wrote called “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.” It was on the Johnny Rivers album where I first heard it. One day, Johnny Rivers invited me up to his house, and Jimmy was there. It was just the three of us. Jimmy sat down at the piano and played “Galveston” and “Didn’t We” and “Sidewalk Song” and, I don’t know, maybe several more. I was stunned. I just sat there with my mouth open listening to these unbelievable songs this guy had written. They were different from anything I had ever heard. I mean the lyrics had a realism to them that just kind of took your breath away.

That night changed my life and the way I thought about songwriting. I started to try to write like Jimmy Webb. I couldn’t do that because I didn’t have his kind of talent. But, with the kind of talent I had, with the kind of songs that I wrote, you couldn’t tell I was trying to write like Jimmy Webb, but I knew what I was doing.

Q: That’s funny. Obviously, you’ll be forever linked to “Midnight Train to Georgia.” It’s one of the biggest hits of all time. It’s a really impressive piece of songwriting. But what was the inspiration for that and were you shocked at the kind of success recording artists have had with that one?

A: I wrote it based on a conversation I had with (actress) Farrah Fawcett. She was dating (actor) Lee Majors, who was a friend of mine. I called Lee one day and Farrah answered the phone and, just during the course of the conversation, she mentioned she was packing her clothes and she was going to take the midnight plane to Houston to visit her family. “Midnight plane to Houston” got kind of stuck in my mind in bold letters. When I got off the phone, I wrote “Midnight Plane to Houston” in about 30 to 45 minutes. I mean, it was right after I got off the phone with her, which was about 5 p.m. or 6 p.m. in the afternoon. I put it on my first album that way.

My publisher, Larry Gordon, was pitching songs to people and he got a phone call from a guy in Atlanta, a producer who was producing Cissy Houston, and they really wanted to cut the song but they asked if we wouldn’t mind if they changed the title to “Midnight Train to Georgia” because it sounded more like an R&B title, and also Cissy Houston’s name being Houston, they didn’t want Houston in the title. So my publisher said, “Yes, that’s fine with us.” We were both in agreement that we would let the artist make the song what they could sing to make it something they could believe.

Gladys Knight wanted to change the title too because they’re from Atlanta, and also the fact that it was a train now opened up a big thing for them with their background vocals. They made it a timeless record, not just a hit record but a timeless record.

Q: What did you think when you first heard the Gladys Knight version?

A: Well, I kind of sat there with my mouth open going, “Is this the song I wrote?” I’d never dreamed of having an R&B record. When I wrote it, I thought it was a country song. So I was kind of taken aback that it was an R&B record, you know? I loved it. I absolutely loved it, but it was so foreign to me when I first started that I couldn’t hardly get used to it.

Gladys would always ask if they could change certain things, if she could move around with melodies and maybe change a word here and there, and I said, “Sure. Make it something you believe in and something you can sell.” She did. I mean she just did. She is an unbelievable singer and interpreter of a lyric, and I feel so fortunate that I was the one who wrote songs for her. She cut 12 of my songs overall.

Q: You were speaking about Lee Majors earlier. I understand he claims you were brought in as a ringer in a Los Angeles flag football league once (joking). Tell me a little about that and also the league, which I understand had a few notable people playing in it.

A: He said what? (laughs) I never heard that before. That’s funny. He actually invited me out to play football with his team. He was already playing with them and when he found out I played quarterback for Ole Miss, he said, “Why don’t you come on out and play with us?” I never thought about being a ringer.

I’ll tell you, it was probably something that saved my life because I hadn’t been doing any kind of exercise and I had gone through some depression, and once I started playing football again, running and playing sports, that depression lifted. I started to feel like myself again.

(Actor) Mark Harmon, who was quarterback for UCLA, played on another team, and we played against them. Also, James Caan, the actor, came out and played with us. He’s a pretty good athlete. He didn’t come out consistently, but one or two times he came out. There were a lot of music business people, behind-the-scenes kind of people. Gary Usher, who had written songs with Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, played with us. I can’t think of anybody else off the top my head, but those were just some of notables.

Q: That’s fascinating. So you played football with “The Six Million Dollar Man” and Santino “Sonny” Corleone from “The Godfather”?

A: Yeah, and Mark Harmon and then some other people. The thing people don’t really realize is that actors, singers and songwriters all have a life away from their career. You don’t think about that. You just think about what you see onscreen, but they’re just people who grew up like I did, playing sports and they continue to play sports.

I’ll tell you two other guys – Mike Mitchell and Dick Peterson, two members of the Kingsmen, who recorded “Louie Louie” – they played basketball with us. Yeah. So, they were just so unassuming. A friend of mine had to come up to me one day and said, “You know they were members of the Kingsmen?” I said, “What?” I asked them, “Did you all play on ‘Louie Louie’?” They say, “Yeah,” you know, which is no big deal, huh? And the funny thing is, I saw them not too long ago on one of those oldie rock ‘n’ roll shows on PBS.

Q: So what’s life like for you these days? Tell me where you’re living and what you’re doing.

A: We live in Brentwood, Tenn., and we have a small farm. My daughter (Brighton) is an animal lover and she wanted horses, so she is working to train horses and she does really well. She’s a heck of a rider. My son (Zach) is a budding quarterback for his high school team. He led his team this year as a sophomore to a 14-1 record. You can look any of his stats up on MaxPreps. You can also see his video on Youtube, his sophomore video. I mean he’s really good and, well, he’s better than I ever was. Right now, he is something else.

I have a studio in my home and I continue to write and I make my CDs here at the house and put them out on the Internet on Amazon or CD Baby or my website, jimweatherly.com. Life is good and it’s quiet and we really enjoy it here.

Q: So, the music nerd in me wants to know what you’re listening to these days? Is there any new music or old music you find yourself playing a lot?

A: I still listen to Jimmy Webb songs. I go back every now and then and listen to the Glen Campbell-Jimmy Webb music. I’m reading a book on Linda Ronstadt right now, and I go back and listen to some of her stuff. She recorded one of Jimmy Webb’s songs called “The Moon’s a Harsh Mistress.” It’s absolutely gorgeous. I do go back and listen to some of the rockabilly music. I listen to Elvis radio on XM Radio. I listen to ’50s and ’60s, some ’70s.

I don’t listen to a lot of the music today except for what my kids bring to me. They’re always trying to find me something I like about today’s music. So I listen and they have pretty good taste. They bring me some pretty good songs that I kind of like. But I’m just a product of the times I grew up in, and music has changed, I guess way too much for me now.

Q: What does it mean to you to be inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame along with people like Donovan and Ray Davies and others?

A: It’s an incredible honor. It’s the highest honor as a songwriter that you can have unless they want to give you some kind of a special award or something like that. Just being inducted into the Hall of Fame with all the great songwriters that are in there and, surprisingly, all the great songwriters that aren’t in there yet, it’s just an incredible honor. I was shocked because it’s something I never would let myself think about because I figured my chances were, if I ever got in, way down the list. So, I was really pleasantly surprised, to say the least.

Q: After all the success you’ve experienced in the songwriting world, do you have any advice for would-be songwriters?

A: I came along at a time when it was a simpler world, so it would be kind of a different path for kids today. I don’t know if I could get into the music business today. First of all, the music is something that is so foreign to me that I wouldn’t be able to really write it. But I guess the one piece of advice I would give young writers is be true to yourself, write what you believe and have a good time.

Q: Do you ever get back to campus or to Oxford much? What are the kinds of things you like to do when you come back?

A: I do get back. We get down to one or two football games a year. My son has had official visits down there (at UM) and I still have family that lives in Pontotoc and Tupelo. I get down to visit them and go over to Ole Miss to some of the games. I would like to get down more often than I do but, you know, raising a family, it’s been tougher to get down to Oxford.

Q: Is there anything else you would like to say about Ole Miss and what this place and this institution means to you personally?

A: It was four, or actually five, of the most wonderful years of my life. It’s a very, very special place. I’ve heard before that people who go to Ole Miss really like the University of Mississippi, but they love Ole Miss. That’s exactly the way I feel. Ole Miss is part of my family, and I appreciate them letting me be a part of theirs.