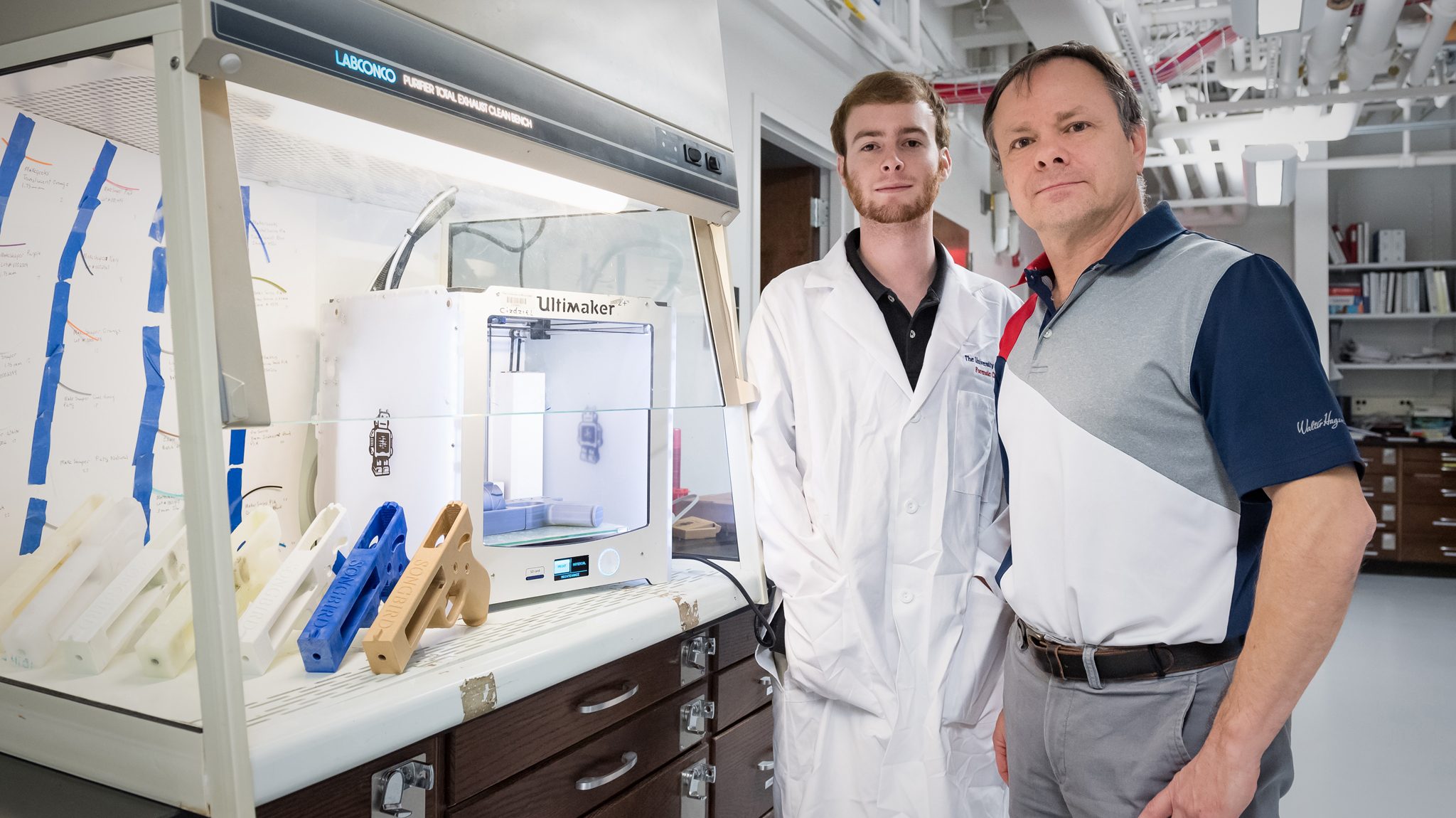

James Cizdziel (right), UM associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and recent doctoral graduate Oscar ‘Beau’ Black have spent two years researching 3D-printed firearms through a grant from the National Institute of Justice, part of the U.S. Department of Justice. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

OXFORD, Miss. – In the summer of 2016, Transportation Security Administration screeners at Reno-Tahoe International Airport in Nevada confiscated an oddity: a 3D-printed handgun in a man’s carry-on baggage.

The plastic gun was inoperable but accompanied by five .22-caliber bullets. The passenger said he had forgotten about the gun and willingly left it at the airport and boarded his flight without being arrested.

The TSA later said the plastic gun was believed to be the first of its kind seized at a U.S. airport.

Since the world’s first functional 3D-printed firearm was designed in 2013, such guns have increasingly been in the news. Proponents of the firearms – 3D-printed with polymers from digital files – maintain that sharing blueprints and printing the guns are protected activities under the First and Second Amendments. Opponents argue the guns are concerning because they are undetectable and also untraceable since they have no serial numbers.

Tackling some of those forensic unknowns are a University of Mississippi chemistry professor and a graduate student. Their research is developing analytical methods to explore how the firearms might be traced using chemical fingerprints rather than relying on physical evidence, with the goal of offering tools for law enforcement to track the guns as they become more widespread.

“We can positively identify the type of polymer used in the construction of the gun from flecks or smears of plastic on bullets, cartridge cases and in gunshot residue collected on clothing,” said James Cizdziel, an associate professor in the UM Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

Cizdziel, who joined the Ole Miss faculty in 2008, and Oscar “Beau” Black, who recently earned his doctorate in chemistry, have spent two years researching 3D-printed firearms through a grant from the National Institute of Justice, part of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The three-year, $150,000 grant, “Physical and Chemical Trace Evidence from 3D-Printed Firearms,” has resulted in a 2017 peer-reviewed paper in Forensic Chemistry, a growing reference library of mass spectra from 3D-printed firearms for use by law enforcement and a book, “Forensic Analysis of Gunshot Residue, 3D-Printed Firearms, and Gunshot Injuries: Current Research and Future Perspectives.”

The world’s first functional 3D-printed firearm was designed in 2013. The guns are 3D-printed with polymers from digital files and are untraceable since they have no serial numbers. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

The research involved Cizdziel and Black being the first to use Direct Analysis in Real Time, or DART, Mass Spectrometry to identify polymers and organic gunshot residue in evidence from 3D-printed guns. The idea is forensic experts could trace the polymer that might show up in chemical evidence from the discharge of a 3D-printed firearm back to the type of plastic used in the gun.

“Our growing database provides a second means of identification or grouping of samples, alleviating the need for subjective interpretation of the mass spectral peaks,” said Cizdziel, a Buffalo native. “We also published fingerprinting protocols on surfaces of 3D-printed guns.

“Overall, we demonstrated that our methods are particularly useful for investigating crimes involving 3D-printed guns.”

The pair’s research arises from an undergraduate chemistry class Cizdziel taught in 2014, Introduction to Instrumental Analysis. Before earning his bachelor’s degree in forensic chemistry in 2015, Black, who also was an undergraduate researcher in Cizdziel’s laboratory, took the class, where talk soon turned to 3D-printed firearms.

“We discussed how developing new reliable analytical methods for forensic practitioners dealing with trace evidence from 3D-printed guns would make a good doctoral research project,” Cizdziel said. “Apparently this sparked a fire in (Black), and he not only joined my research group as a graduate student but was awarded a research fellowship from the Department of Justice to do that very project.”

Black, from Weatherford, Texas, began the project in 2016, before funding was secured in 2017, and quickly realized he was in unexplored territory.

“There was such a dearth of information out there,” Black said. “There was only one, I think, report of an actual test fire (of a 3D-printed firearm) from a forensic agency.”

The pair began creating functional 3D-printed firearms – either .22-caliber or .38-caliber handguns – that used certain metal parts to comply with a federal ban on weapons that aren’t picked up by metal detectors. They test-fired them under controlled and safe conditions at the Mississippi Crime Laboratory in Pearl and the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences in Hoover, Alabama.

“When you discharge them, they do exactly what they are designed to do,” Black said. “You can shoot them multiple times. There was one we shot dozens of times with no visible wear and tear on it.”

The discharges generated samples to analyze. The duo also evaluated the differences in evidence between 3D-printed guns and conventional guns, and used the analytical technique mass spectrometry to identify and characterize the various polymer types in 3D-printed gun evidence.

Research by University of Mississippi professor James Cizdziel and doctoral graduate Oscar ‘Beau’ Black has led to a growing reference library of polymers from 3D-printed firearms for use by law enforcement. Photo by Megan Wolfe/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

This work was the beginning of creating a reference library of various polymer samples to provide the basis of categorizing an unknown sample. The reference library holds about 50 polymer samples.

Cizdziel and Black were assisted in their research by undergraduate students and Murrell Godfrey, director of the UM forensic chemistry program and associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry.

Black graduated Saturday (May 11), but the pair’s research is ongoing, including expanding and improving the 3D-print polymer reference library.

“The ultimate goal would have the reference library in a format that’s similar to the other reference libraries that are out there for fingerprints, etc.,” Black said. “Every different arena has a reference library that goes along with that discipline.”

Beyond work on the reference library, the twosome is examining DNA methods on 3D-printed firearms and studying the longevity of polymer evidence under weathering conditions. Cizdziel and Black also are working on a paper that presents all their scientific discoveries when it comes to 3D-printed firearms.

Not knowing what they might find in their investigations has led to some exciting findings and groundbreaking work, Cizdziel said.

“That’s when things get interesting,” he said. “When you don’t quite know what to expect.”