Group donates memory book about 1962 riots

OXFORD, Miss. – Fifty years ago, as a young U.S. deputy marshal in his twenties, Herschel Garner was sent to Oxford to protect James Meredith’s right to enroll at the University of Mississippi.

“Ole Miss was not nearly as nice and welcoming in 1962 as it is today,” Garner said Monday (Oct. 1) at a program in the UM Student Union ballroom. “It’s wonderful to be met with open arms and handshakes instead of bricks.”

Denzil N. Bud Staple, who was among the 127 marshals also deployed to Oxford that fall, nodded in agreement, recalling that he lost count of the number of rocks and bricks thrown at him on the night Meredith become the first black person to enroll at Ole Miss.

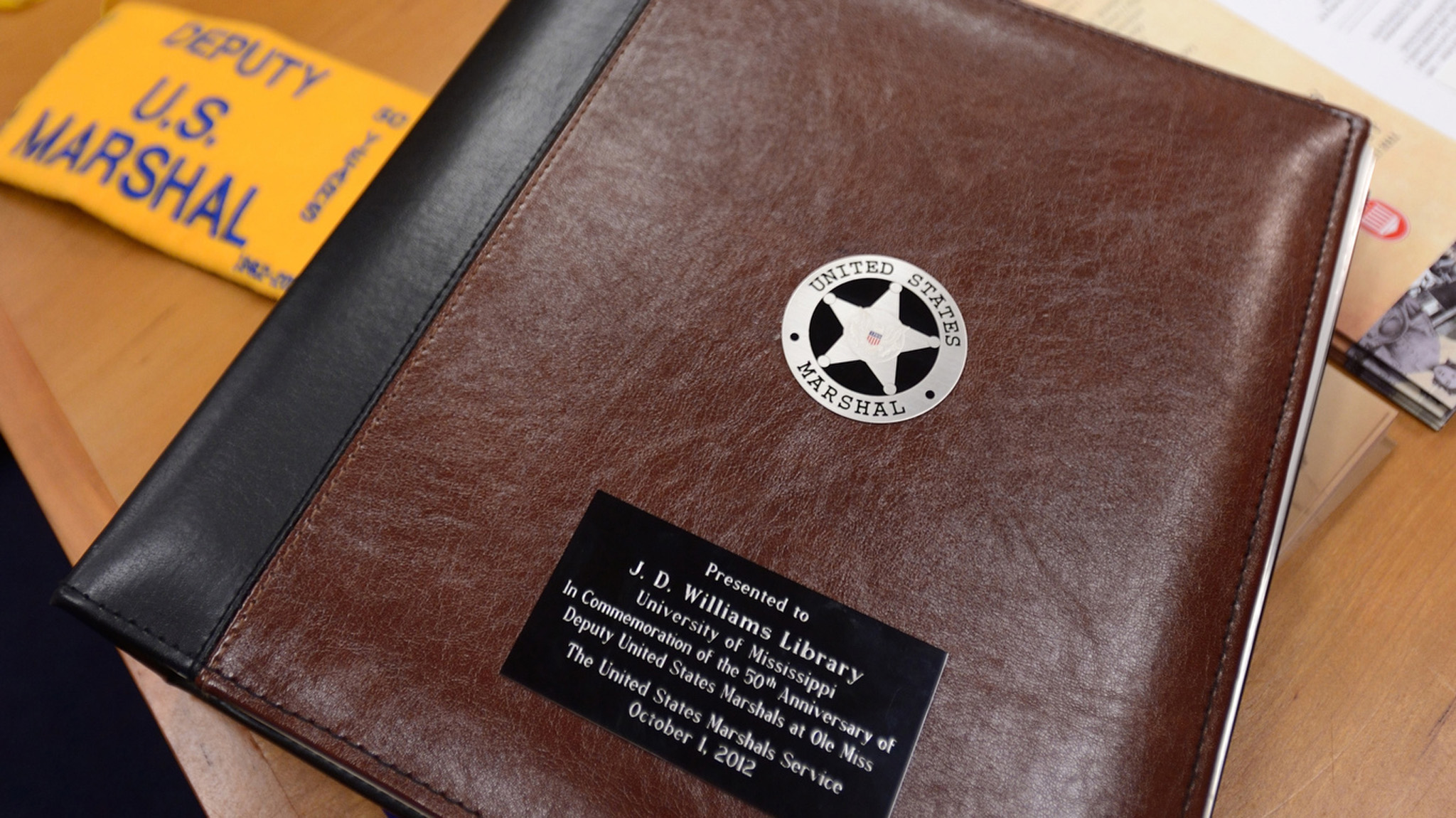

The memory book donated to the University of Mississippi by a group of U.S. marshals contains maps, photographs, codes and a letter dated October 1962 that details the number of injuries during the riots when James Meredith was enrolled at Ole Miss. UM photo by Kevin Bain.

“They threw anything they had,” Staple said. “I was hit with, probably, a brick. Other deputies were also hit. The stones were getting larger. Some had broken concrete chunks slightly smaller than a football with wire handles attached that allowed them to toss the rocks completely across the street – breaking anything or anybody they hit.”

Garner, Staple and several former colleagues participated in a 50th anniversary panel discussion sharing firsthand accounts of the violent confrontation, which left two dead and 79 marshals, plus several border patrol agents, injured.

Earlier, on Sunday (Sept. 30), the marshals donated a memory book about the 1962 integration to the university’s Department of Archives and Special Collections. The book contains maps, photographs, codes and a letter dated October 1962 that details the number of injuries.

Acting as master of ceremonies for the panel discussion, U.S. Marshal Historian Dave Turk said, “History is often made when one person stands his ground and demands to be treated fairly. But in 1962, history needed enforcement.”

By most accounts, the afternoon of Sept. 30 began quietly, with students asking a few questions, Turk said. But by 7 p.m., the crowd grew loud and violent as people from as far away as California joined locals and began hurling racial insults and later throwing rocks, bricks, battery acid and Molotov cocktails.

“But the marshals were ordered not to fire weapons,” he said. “Their job was to see that Meredith was safely admitted to school among a crowd that grew more and more violent as the night passed. If it were not for their training, it would have been a massacre.”

Because the crowd was not adequately restrained by state authorities, the marshal received permission to use tear gas.

The use of tear gas “gained us a little space from the crowd, but only for brief periods,” Staple said. “We were still restricted from using firearms, so basically we were standing targets when the gunfire started.”

A bullet struck Ray Gunter, 23, of Oxford in the head. He died, and authorities never discovered who fired the shot. Paul Guihard, a French journalist, was shot and killed at almost point-blank range by an unknown assailant.

Kirk Bowden, one of a few black U.S. deputy marshals in 1962, said he was only 26 years old when he was dispatched to Oxford in late November or December.

“Many may not realize there were black deputy marshals here back then,” Bowden said. “And I can tell you Oxford was not a pleasant place for federal law enforcement officers of any race, but rioters definitely vented a lot of their anger on us black marshals. As soon as I stepped foot on campus, I thought, ‘Lord, what have I gotten myself into?'”

The Kennedy administration did not send black marshals to Oxford in September or October, fearing that their presence would further inflame the crowds opposed to the integration, Turk said.

Following the initial confrontation, Luke Charles Moore was the first black U.S. marshal in Oxford. Moore worked directly under Chief Marshal James McShane and U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, supervising, coordinating and monitoring the U.S. marshals’ activity in Oxford. In his supervisory capacity, Moore traveled to Oxford many times, although few knew of his role and his visits at the time.

Once Meredith was enrolled, Bowden and seven other black marshals were assigned to his security detail on campus.

“At the time, I was wondering why a veteran, a taxpayer, needed protection to attend a state university,” he said. “It didn’t take me long to discover the answer to my unspoken question. The death threats came daily. The racial slurs too, and I can’t forget the rocks and stones thrown out of cars and windows when Meredith walked to and from classes.

“This one day, Meredith and I went to a local clothing store. The white guy before us gave his credit card, paid for his purchases and left. But when Meredith presented his credit card, the saleslady asked for identification. I said to her, ‘Do you really think any Negro would be impersonating James Meredith? In Mississippi?’

“I know Meredith doesn’t think he’s a hero, but what else do you call someone who stood up to right a wrong. He fought the system and paid a price for freedom.”

Stacia Hylton, director of the U.S. Marshals Service, agreed and added that the history of this state and nation changed forever when Meredith enrolled at Ole Miss.

“Meredith was a leader in his own way, but so are these U.S. marshals who protected the integrity of justice and upheld the law with pride,” Hylton said. “As President Kennedy said that deadly night, ‘Americans are free, in short, to disagree with the law but not to disobey it. … If this country should ever reach the point where any man or group of men by force or threat of force could long defy the commands of our court and our Constitution, then no law would stand free from doubt, no judge would be sure of his writ and no citizen would be safe from his neighbors.'”