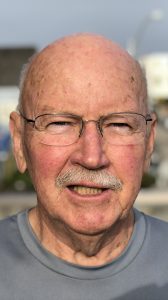

Charles A. ‘Charley’ Calhoun (BSCE 61) enjoys sharing stories from his half-century-long career with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Submitted photo

Charles “Charley” A. Calhoun (BSCE 61) never set his sights on becoming well-known. Yet, the University of Mississippi civil engineering alumnus’s career has made him somewhat of a living legend within the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, where he was employed for more than 50 years.

“My father had a strong influence on me,” said Calhoun, who was born July 4, 1939 in Hattiesburg. “I remember when I was in about the 10th or 11th grade, we would sit down on the back steps talking about careers. He asked me what I wanted to study when I went to college.”

While Calhoun assumed he would go to college, he didn’t determine his major beforehand.

“My father thought civil engineering was the best career,” he said. “I got into the technical aspects of civil engineering and discovered that, to a large extent, he was right. It’s been a fascinating profession and one that has served me well.”

The Calhoun family moved several times during Charley’s early years. His father was a civil engineer for the Mississippi State Highway Department. During World War II, he briefly worked for the Corps of Engineers in Louisiana before returning to his wife’s hometown of Lucedale, Mississippi, and working in the shipyard in Mobile, Alabama, until the war ended. He then returned to Hattiesburg where Charley grew up and graduated from high school.

Calhoun’s father was a UM alumnus who earned his degree in 1927. Thirty years later, Calhoun followed in his father’s footsteps.

“The Ole Miss School of Engineering is made up of many wonderful stories of connections that have brought people together at different times for similar engineering educational experiences at this flagship university,” said Marni Kendricks, assistant dean of undergraduate academics in the engineering school. “We always enjoy meeting and hearing about our legacy alumni because of the deep-roots commitment to their alma mater. For Ole Miss Engineering to be an integral part of this family for so many years, we consider it to be a very, very special honor.”

During his junior and senior years at the university, Calhoun worked part time at the USDA Sedimentation Lab. Following graduation, he began a long career working for the Bureau of Reclamation.

“Dean Kellogg told us the Bureau of Reclamation offered some of the best engineering professional opportunities anywhere,” Calhoun said. “As I learned more about the mission and the program of the Bureau of Reclamation and the work in water resources, it had a great deal of appeal to me.”

Calhoun was offered a job with the bureau after graduation in June 1961. He went to Denver and worked there in a variety of jobs.

“I got in some real neat foreign activities,” Calhoun said. “There was a great deal of interest in the Soviet Union. We entertained Soviet engineers over here with Deputy Commissioner Ed Sullivan, and accompanied him over to the Soviet Union for a couple of weeks in ’74.”

Calhoun also went to Spain for a couple of weeks in early 1975, and entertained Spanish engineers visiting the U.S.

“We were looking for ways to achieve an operation of open-channel canal systems,” he said. “I was expected, and fortunate, to have the opportunity to go through a one-year rotation program. So I spent three months in canals and pipelines, I spent three months in contract administration doing construction contract work, three months in the soils lab over in soil mechanics, and then three months out in California in Los Banos doing some fieldwork, pre-construction and construction work.”

Calhoun remembers the drought of 1976-77, which was one of the worst droughts since the ‘30s, throughout most of the Western United States.

“We got into a legal confrontation with the City of Denver,” Calhoun said. “The City of Denver was diverting water out of priority beyond their entitlement at Dillon Reservoir that affected our ability to store water at Green Mountain Reservoir as part of the Colorado-Big Thompson project. And so I got involved very deeply with the Solicitor’s Office, Justice Department, pursuing possible litigation to protect the reclamation rights-project rights.”

Calhoun said he was taken from a somewhat sheltered career in the technical areas into the world of politics, law and management in a two-year period.

“All this was going on, and I realized how fortunate I was to have this type of opportunity and looked on it as a real challenge,” he said.

Calhoun was promoted to chief of water, land and power for the Southwestern regional office of the Bureau of Reclamation in Amarillo, Texas, in 1980. He remained in that position for three years before being transferred to Albuquerque, New Mexico, as a project manager.

“I stayed there nine years and went to Boulder City, Nevada, as assistant regional director,” he said. “I was there a couple of years and then moved to the regional office in Salt Lake City, Utah.”

Calhoun’s positions and assignments also included his being appointed federal commissioner and chairman of the Pecos River Commission from 2003 to 2010.

“The bureau was considered in some ways almost a graduate school at that time for young engineers,” Calhoun said. “You could come into the bureau and get some very good experience if you were fortunate enough to work in a more enlightened area.”

Calhoun considers the Meritorious Service Award that he received from the U.S. Department of the Interior in 2000 his highest professional honor. He said he owes a lot to his education and sees value in continuing to support his alma mater.

“I see it as my payback for an outstanding education,” he said. “I told my kids many times that I think everybody should pursue their education to whatever appropriate level, because education is almost a holy quest and you should be knowledgeable. It’s great to have a profession, but the people who get things done in this world are usually the people who can work the other people in some sort of team arrangement or some sort of an organizational arrangement.”

Calhoun and his wife, Paula, reside in Orange Beach, Alabama, and spend summers in Sandy, Utah. Calhoun’s hobbies include reading, walking, gardening, and applying engineering principles to drainage problems in Orange Beach. The couple has five children (all of whom have bachelor’s degrees and three with master’s degrees) and three grandchildren, “who sure are a joy,” Calhoun said.